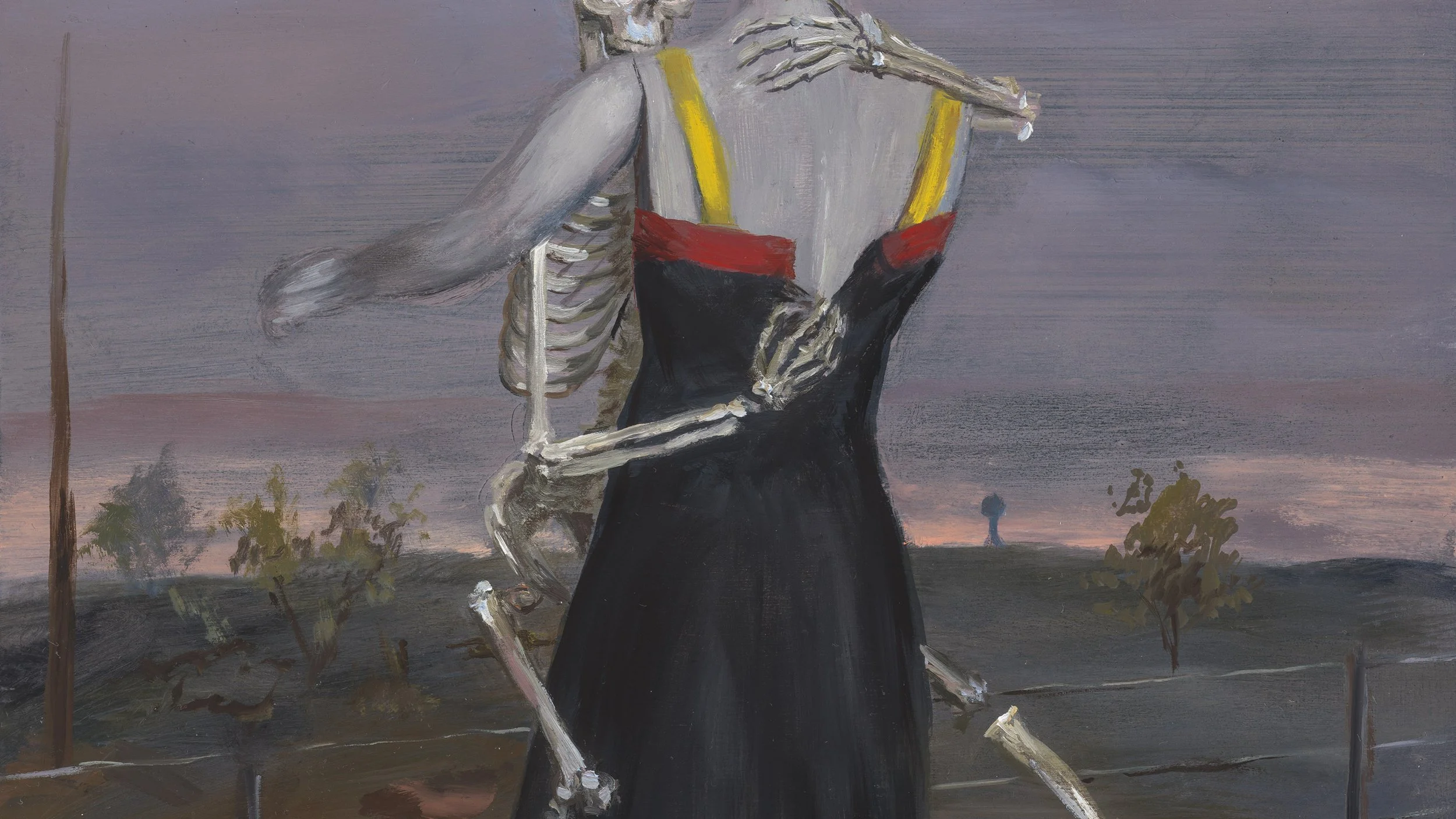

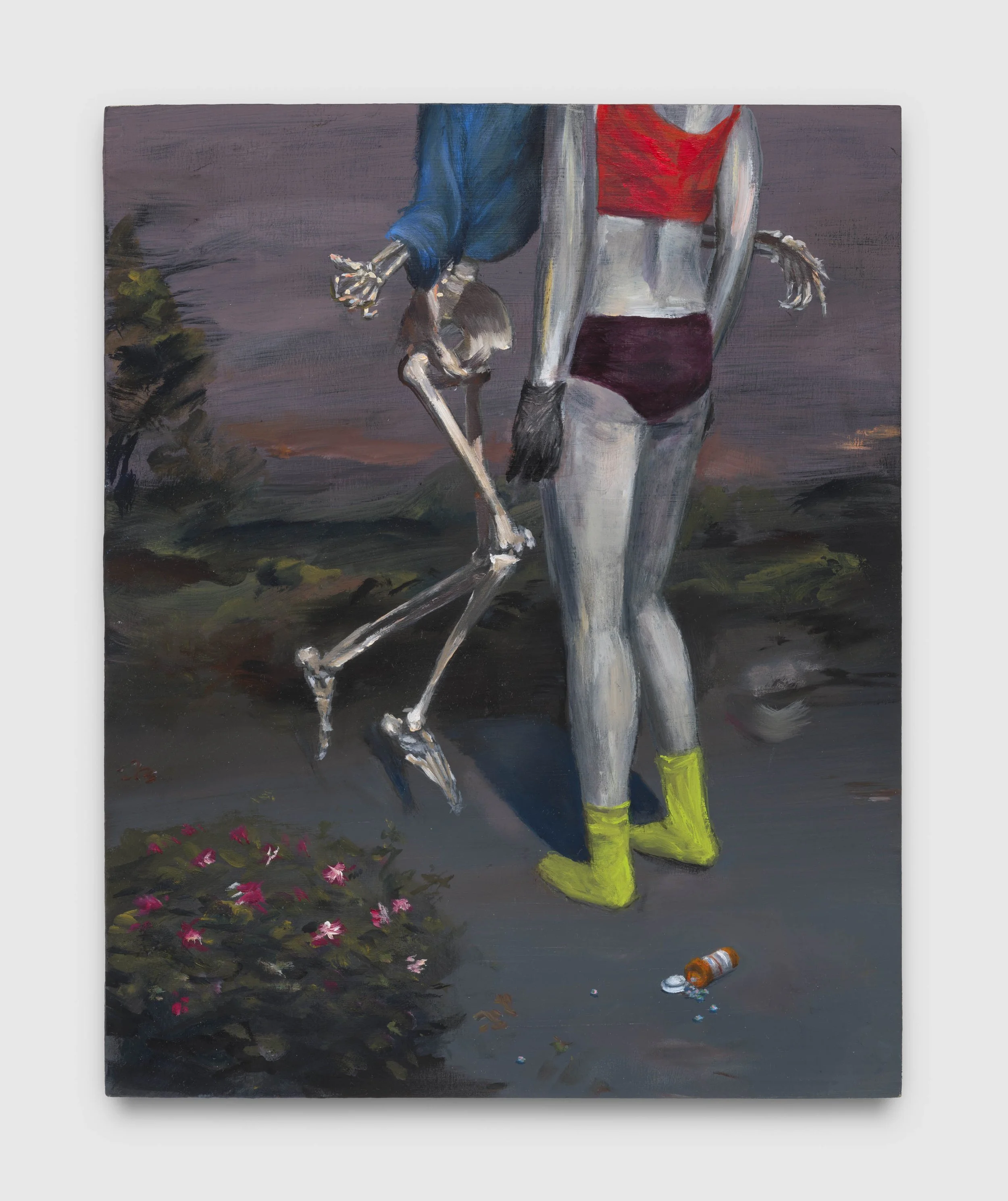

Rhyse Ziemba

Be not too hard

January 6th - 27th, 2024

“…a person who once was alive but now is not and yet they smile so persistently. It's as if they know something we don't – something hilarious.”

Statement from the artist:

For these paintings I started with a simple method:

Make a still-life of non-human figures from direct observation.

Contrive a background (generally a loose remembrance of a real location).

Re-work the figures until the painting feels alive.

I am not usually (nor do I aspire to be) an especially methodical artist but in this case it felt good to work from a plan. I have always appreciated in others and tried to cultivate within myself the “intuitive/synthesizing/joining-together” state of mind that is a huge part of art. It's what many people mean when they use the word creativity. But almost as important is its opposite – the “analytical/articulating/segmenting” part. It is only with great effort and years of struggle that I have come to appreciate the creativity of constraint. In art as in life, it is necessary to sometimes push and sometimes pull (of course, the difficult thing is knowing when to do which and how much and for how long). Painting is excluding what is not in the picture no less than including what is. To depict reality realistically means depicting the limits of that reality. A painting is a translation and therefore a compromise: of time, space, and the shortcomings of translation itself, its bycatch and distortions.

Despite these systematic concerns, the descriptive element for these paintings came to me intuitively. Sometimes I could understand one layer or the other quickly but usually the relationship between me and the painting as well as the relationship between the figures and their environment developed holistically and gradually. I worked at a pace that gave all parties enough time to move towards each other but not so much that they might stop moving altogether. These paintings are negotiations. Each succeeds insofar as it transcends its initial contrived existence, i.e. insofar as I succeed at fooling myself into momentarily believing what I know to be false. The only way I know how is to look for and try to honor and recognize the arrival of the unexpected moment.

These paintings, which suggest motion but do not move and show depth even as the figures push against the flatness of the picture plane, subvert the reality of time and materiality in order to capture the same. Likewise I use non-human figures to portray human experience. I've always felt persuaded by art like that – where paradoxes tell the truth. Irony and interpretive flexibility can crystallize the mysterious distance between how the world is and how it feels. This way of thinking (perhaps a psychic survival mechanism) is realized splendidly in the image of the skeleton. Indeed I believe the primary explanation for the appearance of skeletons in so many diverse artistic traditions is the delicious and grotesque irony they present. They denote a person who once was alive but now is not and yet they smile so persistently. It's as if they know something we don't – something hilarious.

I started painting skeletons after a few years of exploring the use of non-human characters to tell human stories. This direction was itself a compromise. I wanted to paint from direct observation but felt constrained by the practical difficulty (as well as the ethics) of using human models. I also wanted to make art exploring the slippery distinctions between nature and humanity, and between experience and materiality. Then (as if by natural selection!) the chairs, buckets, and traffic cones in my studio evolved into a rotating ensemble of characters. One day I saw a model of a skeleton in my orthopedist's office and (plunging into the uncanny valley) have been painting them ever since. Because of the process by which I came to paint them, I have idiosyncratic views of what skeletons mean in art. Sometimes these views seem impossibly feeble when measured against the extensive history of skeleton iconography from all over the world. Their meaning is so deeply ingrained and determined by cultural history - by the heavy metal album covers and tequila advertisements we find in commercial visual culture, and also by the Tibetan scrolls, Mesoamerican codices, and old European paintings we see in books and museums – that it overwhelms whatever subtle specific meaning I may intend. Here too is a constraint and so an opportunity to negotiate.

The interesting thing to me about skeletons is not their connotation of death but their utility to life. Think now, dear reader, of your own skeleton. It's almost like a separate individual that lives inside you - a purely mineral being - one that goes everywhere you go and does everything you do. It's the most obviously material part of your body and its very alienation from the subjectivity of consciousness allows you to define your existence against it. Consider your fingernails. They are part of your body yet you can't feel them. Although they grow conspicuously, they don't seem entirely alive. Their thing-like quality is what allows you to grasp and manipulate the other things of the world. As in art, our bodies need something to push against in order to get anywhere.