“There are many aspects of ourselves that are revealed through the creative process. Images emerge through drawing, and their meaning often becomes clear only after completion and reflection. When painting is done without forethought, it can function as a way of unveiling layered personal narratives.”

Emet Sosna

TV: Emet, I’m excited to learn more about your work, thank you for doing this interview. We first met several years ago, like 2010 or so, in NYC, and then reconnected when I first opened the gallery. You were in the very first show we did in June of 2022. I was always struck by how identifiable your work is because it does have a particular style that is all your own. What makes your art part of “you”? Why is your artwork special to you?

ES: There are many aspects of ourselves that are revealed through the creative process. Images emerge through drawing, and their meaning often becomes clear only after completion and reflection. When painting is done without forethought, it can function as a way of unveiling layered personal narratives.

In my practice, I often believed my work was guided by a conscious, cohesive dialogue, only to later discover cryptic elements and a meta-narrative. The act of painting prompted me to recognize latent narratives within myself, allowing my interpretations to become more nuanced and complex over time. As a result, my work became increasingly biographical, though not in a literal sense.

If someone kept a dream diary for their entire life, it would likely be unrecognizable when compared to the major achievements and milestones that typically define a biography. In this way, my work presents unconscious narratives as more revealing, offering insight beyond the surface of conscious experience.

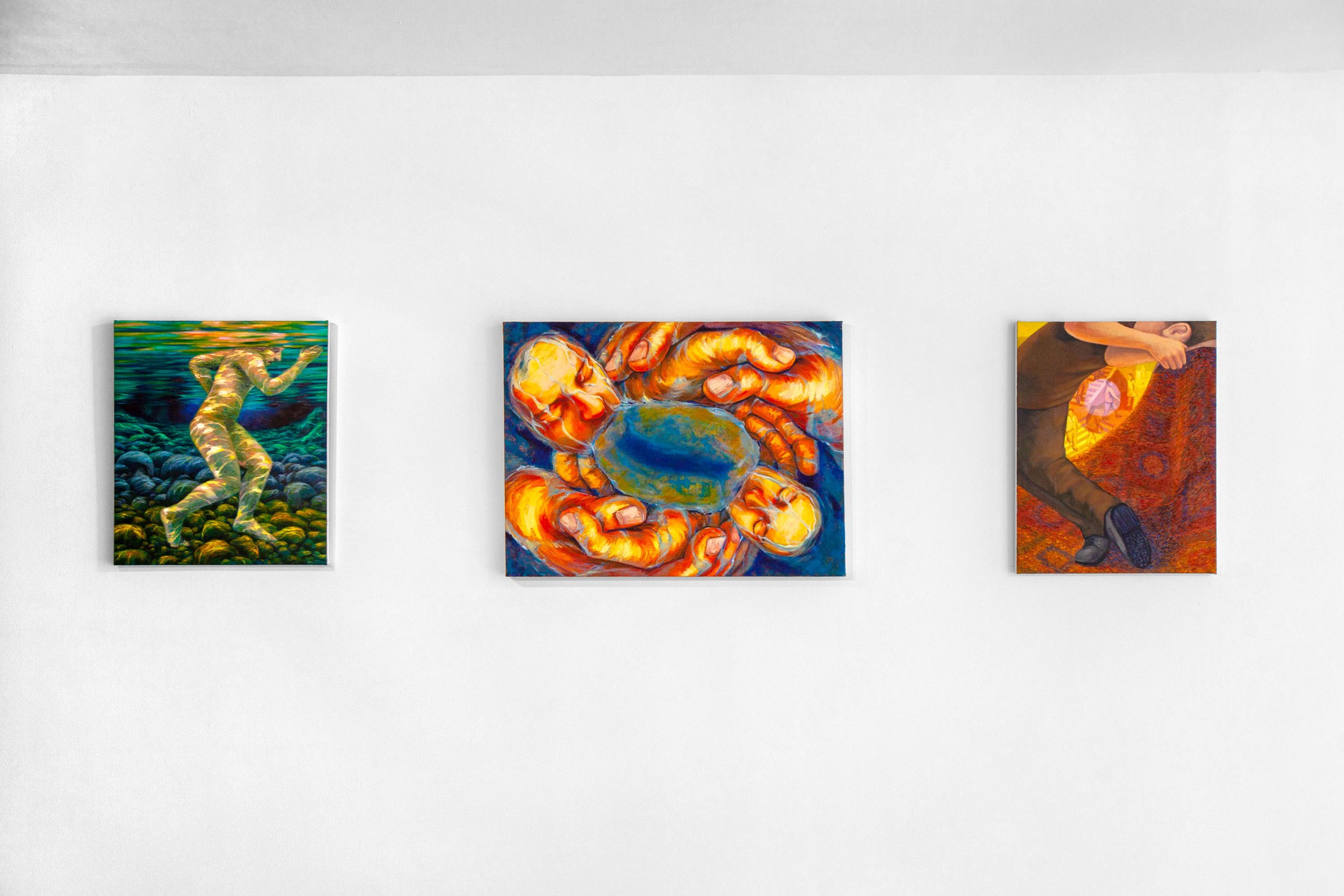

Installation view from Perfect Strangers exhibition, Thomas VanDyke Gallery, 2022

TV: It’s really cool to think about you analyzing your own work in a way that reveals things about yourself you didn’t realize you were putting into it while you were creating it. It would be interesting to compare an artist’s biographical narrative only through their work and separately through their public life and analyze the dissonance or consonance. How do you place your own work in a broader historical context?

ES: I place my work within a much longer historical continuum than is typically used to define art history. I see the origins of art not as beginning with Western traditions, but with symbolic thinking itself. Conventional art history often frames Western art as a starting point, followed by Modernism as a reaction, and then contemporary artists situating themselves into a constructed art historical context. I see art as existing far earlier, possibly even before modern humans.

The earliest art object can be understood as a manuport: a found object that has not been altered but is imbued with symbolic meaning. The Makapansgat pebble is a jasper stone found in a cave in South Africa that resembles a human face. This stone was discovered alongside a three-million-year-old Australopithecus skeleton, an ancestor of Homo sapiens. The jasper pebble originated hundreds of miles away, suggesting it was deliberately carried, likely because of its perceived resemblance to a face. The Australopithecus carried, the found talisman-like face pebble, and then died with it in a cave. This act of recognition and primal meaning-making is far earlier than traditional art history.

My work operates free from overt historical or cultural signifiers that are often used to locate meaning. In this sense, it aligns more closely with pre-historic, pre-literate forms of expression. The work does not rely on literal interpretation, but instead invites subjective experience and unconscious association. While I have been working this way for many years, I believe it is increasingly relevant in the context of AI, which is fundamentally literal, has a tendency towards tropes and is dependent on existing content.

TV: I never thought of having the ability to make creative recognition as an artist concept, but it makes total sense, and is not far from some contemporary conceptual art. Most people think of art as intentional, with the artists acts taking some kind of physical form. Do you think the act of creating is more or less important than the end result?

ES: The act of creating is essential, but so is allowing the finished artwork to exist, even if it is never seen by an audience. Once a work is made, it has a life in the psyche. The artist experiences it, and that experience is inherently transformative.

There are, however, different kinds of art. Work that prioritizes audience appreciation or aesthetic beauty may carry less psychic weight. Its appeal often lies in the power and magnetism associated with aesthetic recognition rather than in inner transformation. It is interesting that artwork is frequently considered finished once aesthetic resolution is achieved, even though the initial impulse behind creation may not be aesthetic at all.

My own work does not begin with aesthetics. It begins in a place of uncertainty, like entering a pitch-dark room and feeling one’s way through it. As the structure and content of the room gradually become discernible, meaning emerges. Only then do beauty and audience appreciation appear as a result, rather than as a goal.

All artists work within a kind of darkness, though some bring a preconceived image of the room into it and project it outward, mistaking the projection for discovery. My practice remains rooted in discovery itself, allowing the work to reveal what was previously unknown.

TV: It sounds like you keep an open mind while beginning a project, and follow your motivation for what feels right rather than focus on achieving a result you already have in mind. In this way, has your work ever resulted in something you never intended or hadn’t expected?

Muddled to Clarity, Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, United Nations, New York

ES: I have surprised myself by realizing that the unusual figures appearing in my work were manifestations of unresolved material from my past. This recognition emerged when I spent time looking across dozens of sketches and paintings in my studio, suddenly connecting them to a recent dream. The realization arrived as an epiphany, revealing a coherence I had not consciously intended.

This moment was important because it showed me that the act of making art was generating a kind of psychic energy, one that allowed me to understand something inaccessible through conscious thought alone. The experience was deeply unsettling, but also clarifying. As a result, my practice shifted and I began working more with sculpture rather than painting, responding with physical materials to the intensity of that discovery.

TV: That takes a certain kind of awareness to recognize and channel into something new. As an artist, do you have any mechanisms for self care and development? Like, do you continue to actively learn new things, practice, or study?

ES: I take care of myself as an artist by remaining in a constant state of making and exploration. I keep multiple sketchbooks, which function as spaces for reflection and discovery and places where I allow myself to work through ideas that do not yet make sense. I maintain separate notebooks for drawing, material experimentation, watercolor, layered studies using tissue paper, and photography. Each serves a distinct purpose in my process and supports sustained inquiry rather than finished outcomes.

Through these ongoing studies, I explore different ways of handling paint and layering, allowing the material itself to generate narrative. Learning and experimentation are central to my practice. I continuously research and test new materials for sculpture, including variegated metal gilding leaf, glass melted over glaze, and high-temperature papers used in the kiln to prevent adhesion between glaze and glass. This commitment to experimentation keeps my practice evolving and supports both my artistic and personal well-being.

Belmont Backstretch Mural, Belmont Park, Long Island, New York

TV: I love that you feed your mind and what you get is creative material, not different from a focused diet and resulting physiological outcome. So, in your work, what do the interactions you depicted represent if not what they depict physically?

ES: The interactions in my work show figures engaging with objects and architectural spaces in ways that are often dysfunctional, confused or entrapping. These interactions symbolize both psychological disorientation and broader societal dysfunction. The characters appear absorbed within their own internal worlds, attempting to navigate systems that have become separated from their original purpose or intention. In this state, function collapses into confusion, and familiar structures become obstacles rather than supports.

TV: This is really a lot to think about having seen many of your paintings and sculptures and wondering about some of the mysteries behind everything you described. It’s great to get a deeper understanding of the catalyst behind your ideas.