Friese Undine

Schreberismus (And the Voluptuous Affliction)

September 2nd - 30th, 2023

“It remains for the future to decide whether there is more delusion in my theory than I should like to admit, or whether there is more truth in Schreber’s delusion than other people are as yet prepared to believe”

- Sigmund Freud

Friese Undine (b. 1965 Los Angeles, California) carves into painted aluminum using a process he developed over a period of years while experimenting with materials and methods of creating images. He also has a penchant for building sculptures from found objects, repurposed items, and mementous relics.

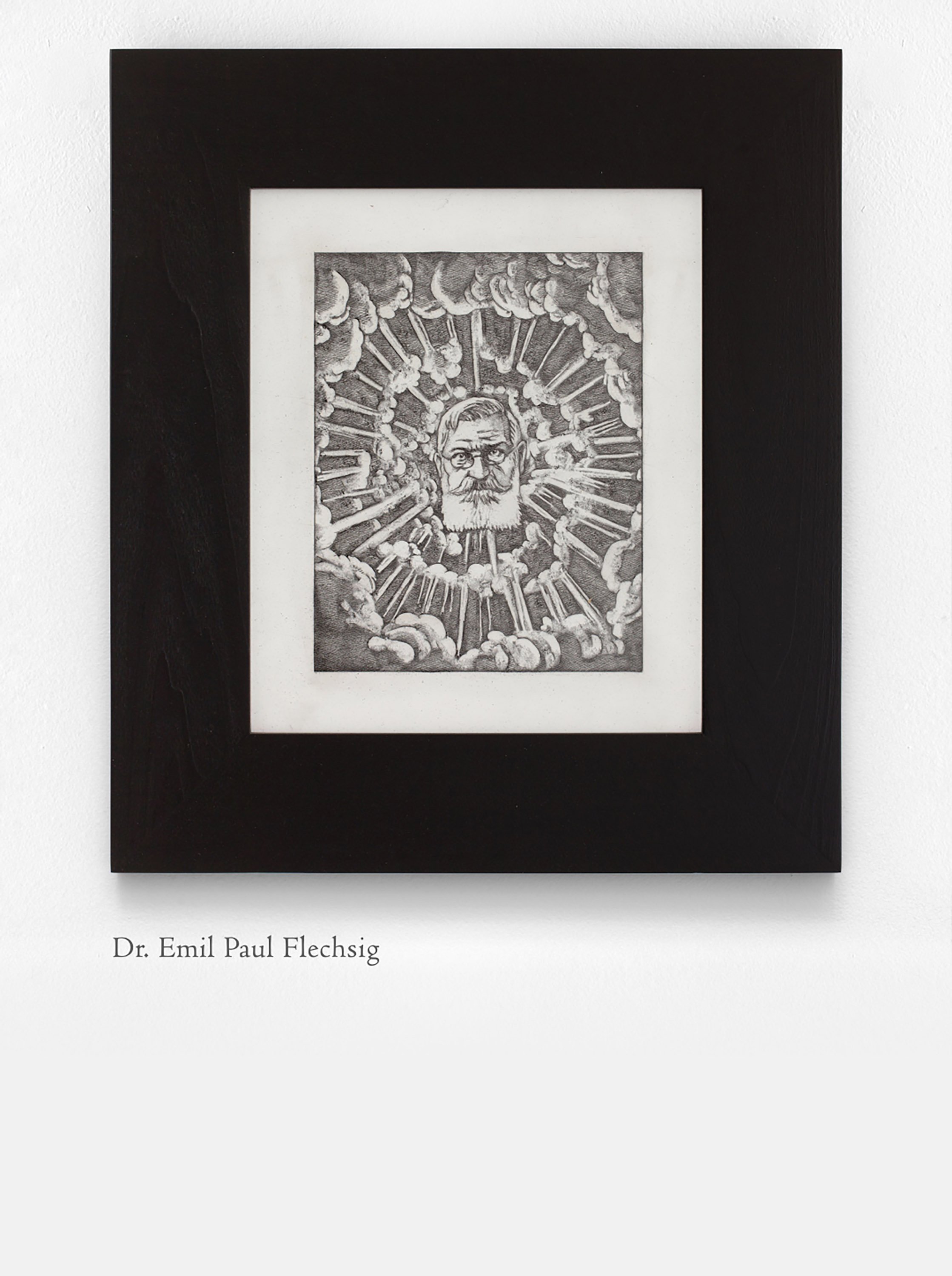

The exhibition Schreberismus and the Voluptuous Affliction features 26 works from the Schreberismus series, a visual deep dive into the writings of Daniel Paul Schreber, and 12 works from The Uncanny series, an examination of the various microscopic organisms making us their biome. There are also several sculptures that include audio elements and written text, inviting participation.

The show title Schreberismus and the Voluptuous Affliction comes from the last name of the man at the center of the series, and the suffix “-ismus” which is the German (and originally Latin) translation of the suffix “-ism”. The word “voluptuous” is one used and talked about by Schreber in his writings. To Schreber, his voluptuousness was a divine gift and was his only escape from his torments.

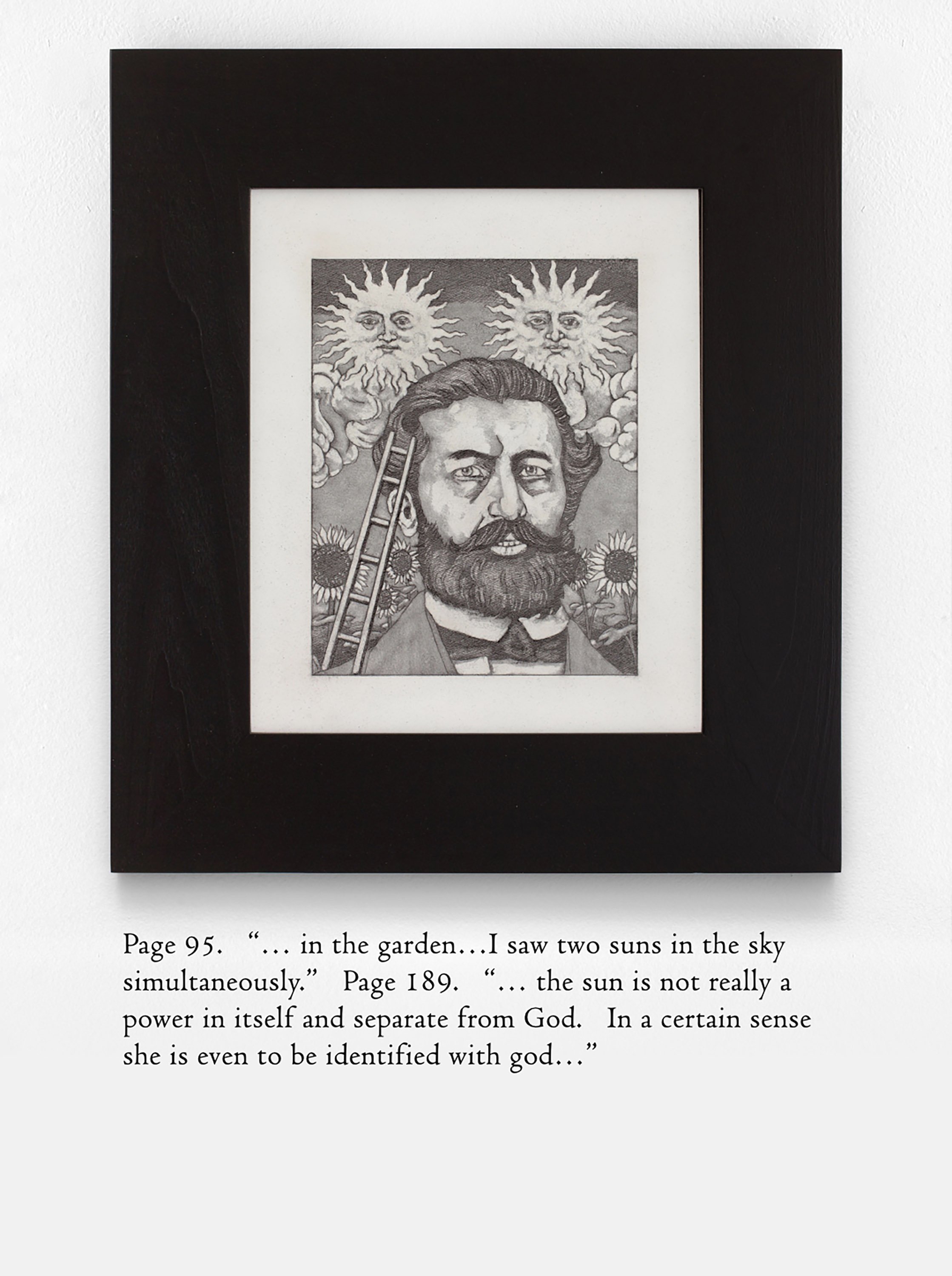

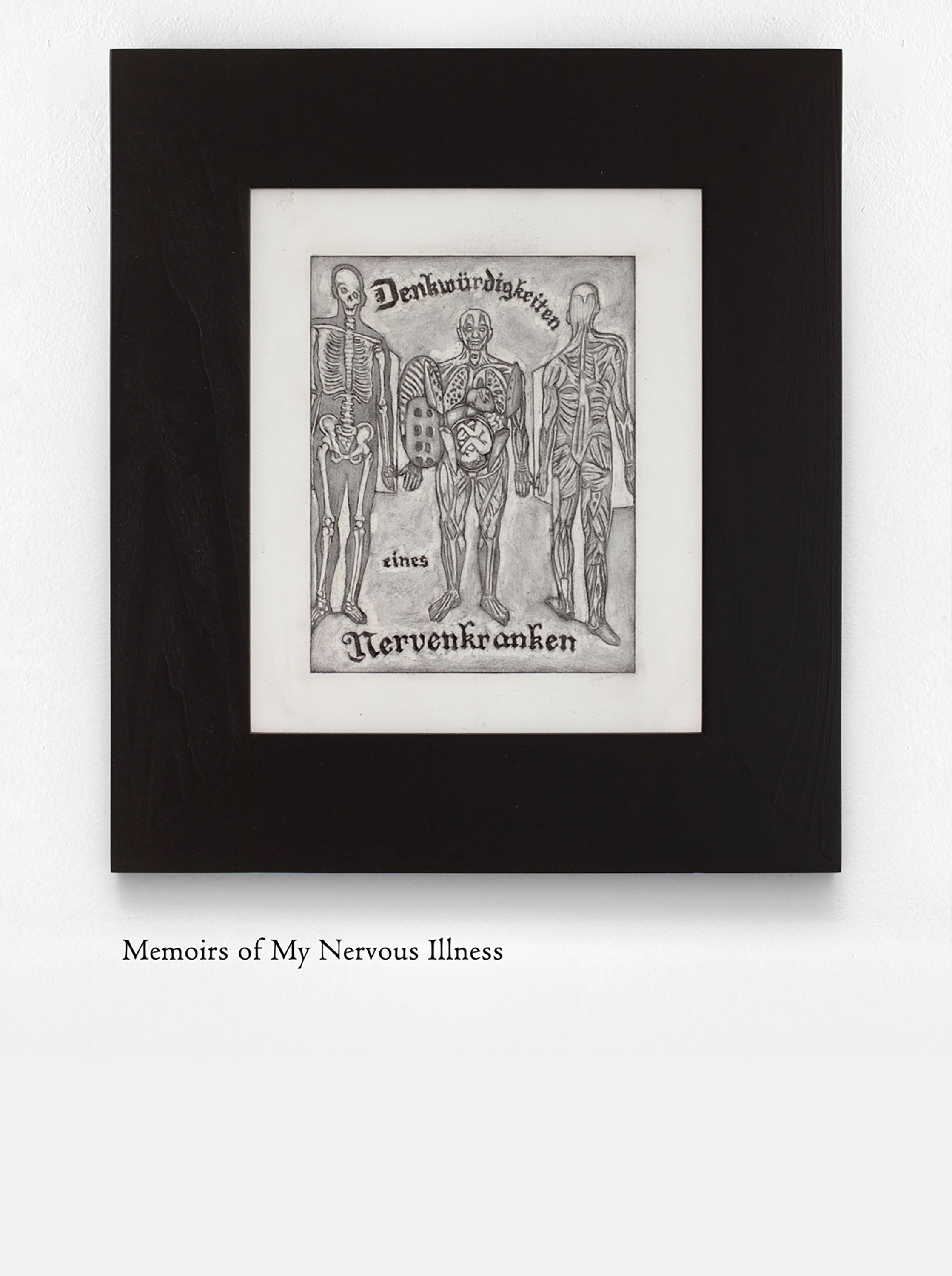

Daniel Paul Schreber (left), Denkwürdigkeiten eines Nervenkranken - Autobiographische Dokumente und Materialien (right)

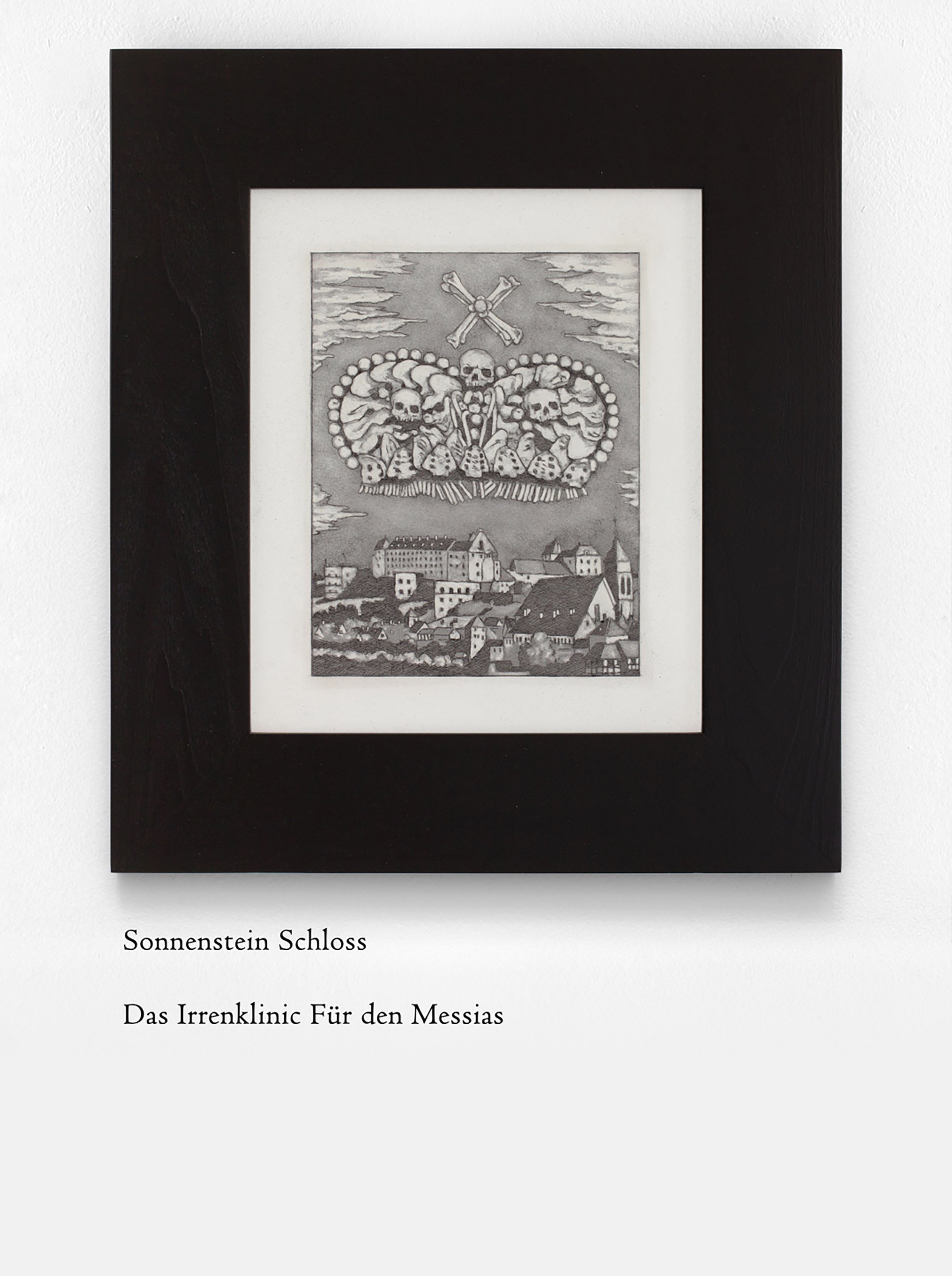

The Schreberismus series is Undine’s interpretation of Daniel Paul Schreber’s memoir My Nervous Illness, written by Schreber in 1885 while he was hospitalized at Sonnenstein Schloss, a mental asylum near Dresdin, Germany. Schreber, who started his career as a lawyer and later became a judge, suffered a mental breakdown from what we now call Schizophrenia. At the time, there was no context for such an ailment, and no conversation around the reality of what people with mental illness were experiencing. Schreber recognized the importance of communicating his own perception of reality in order to help others form a basis for research and treatment. His writings have been widely studied, and helped establish groundwork in the emerging field of psychology and mental health.

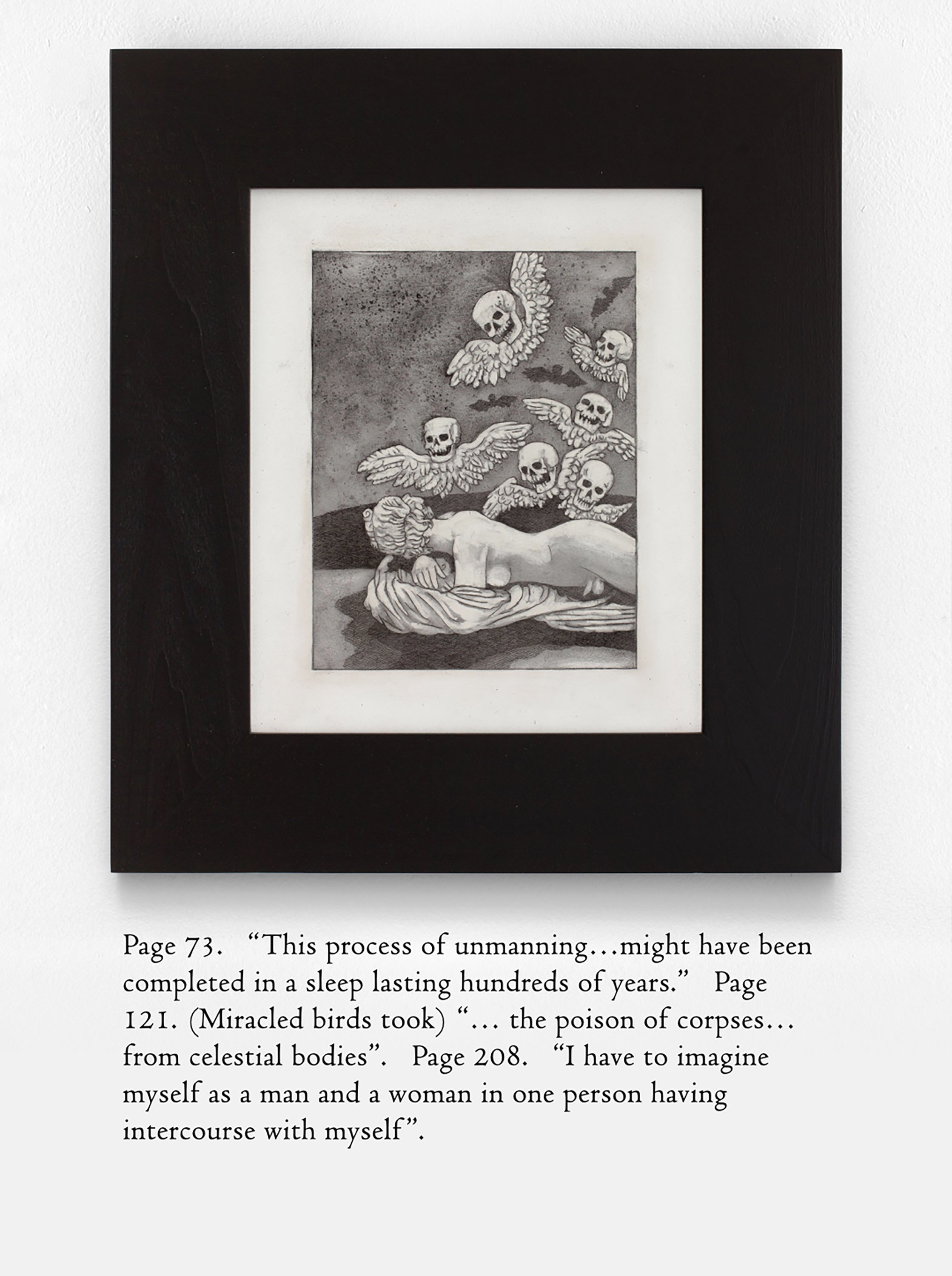

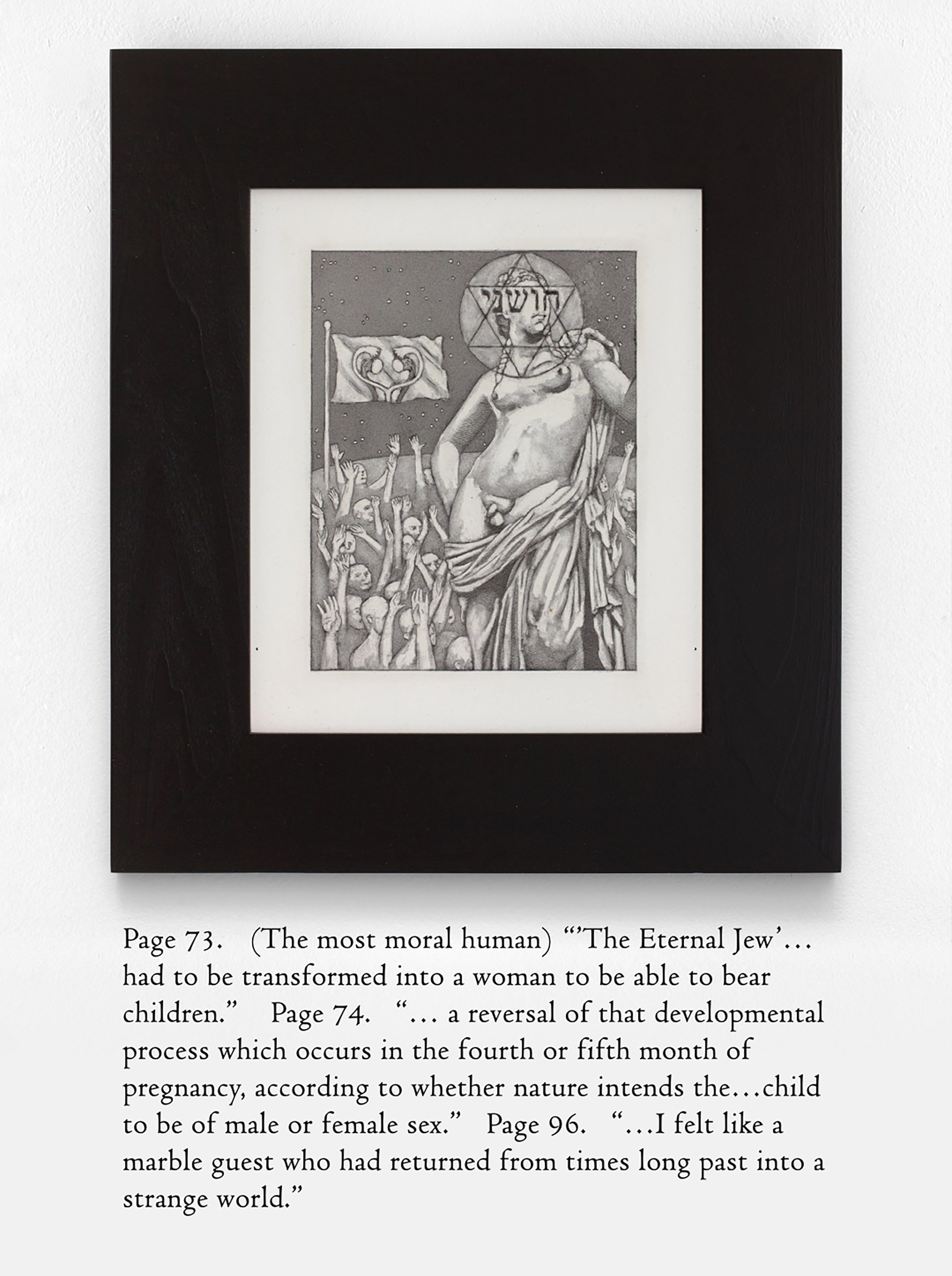

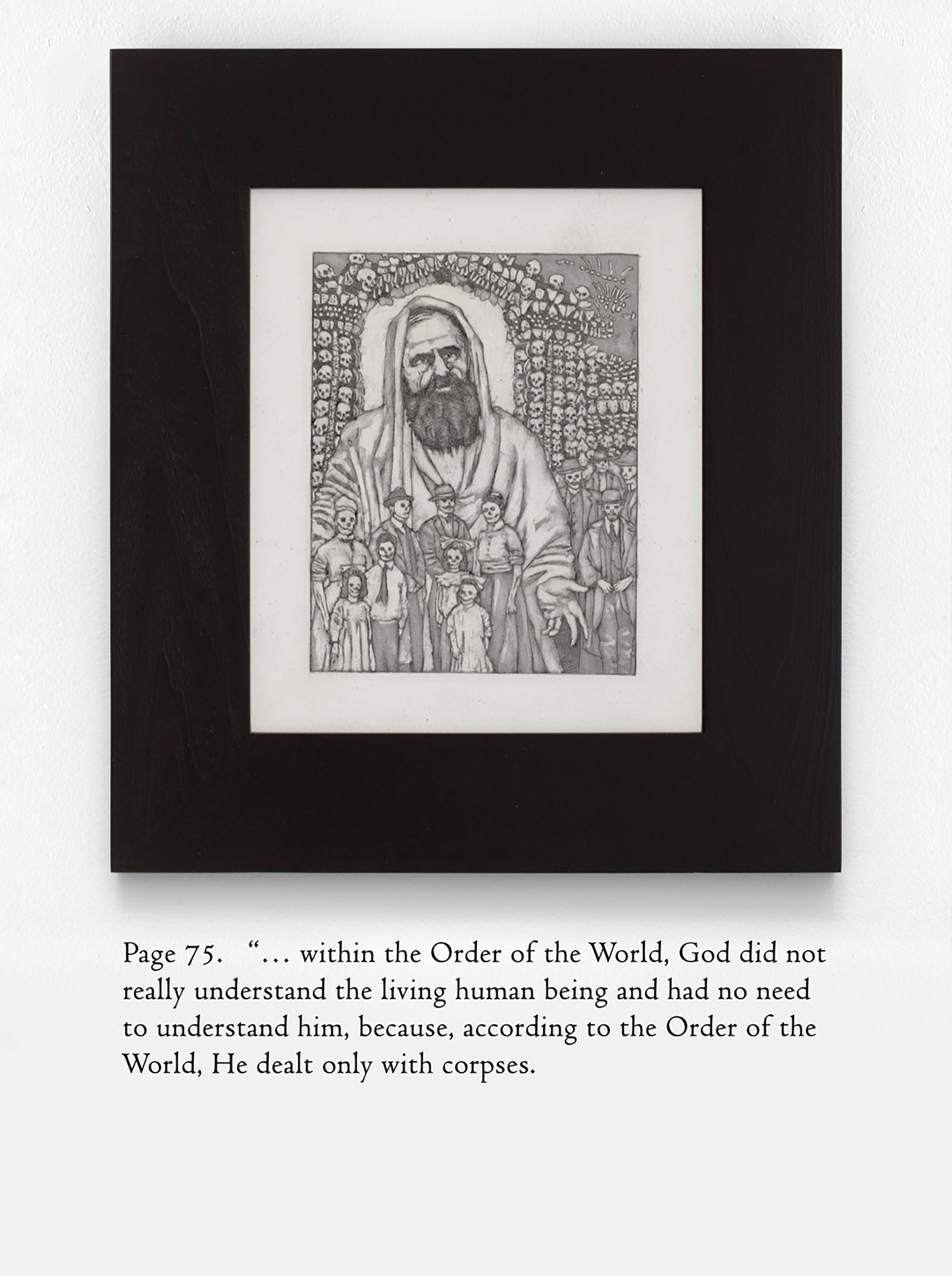

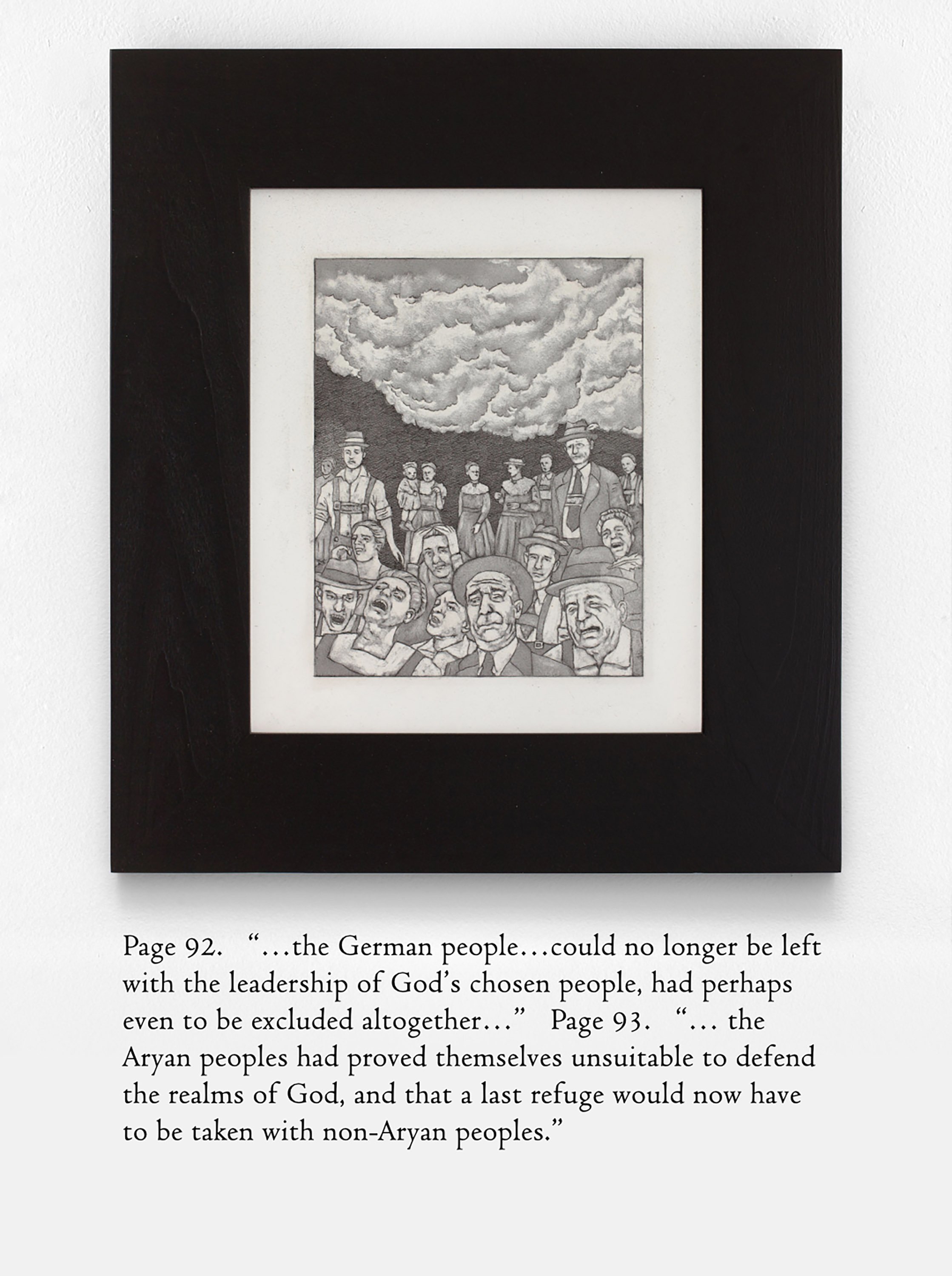

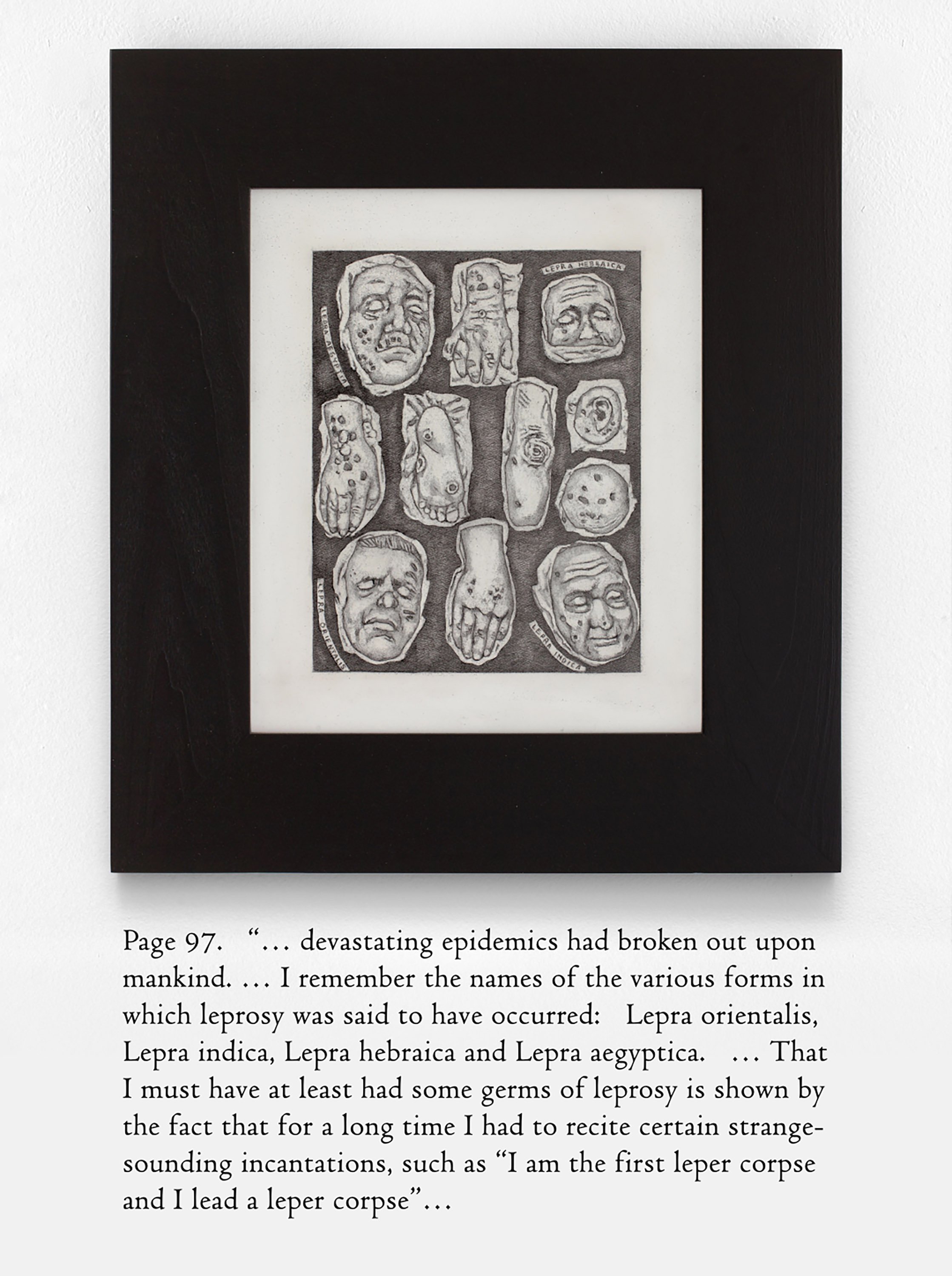

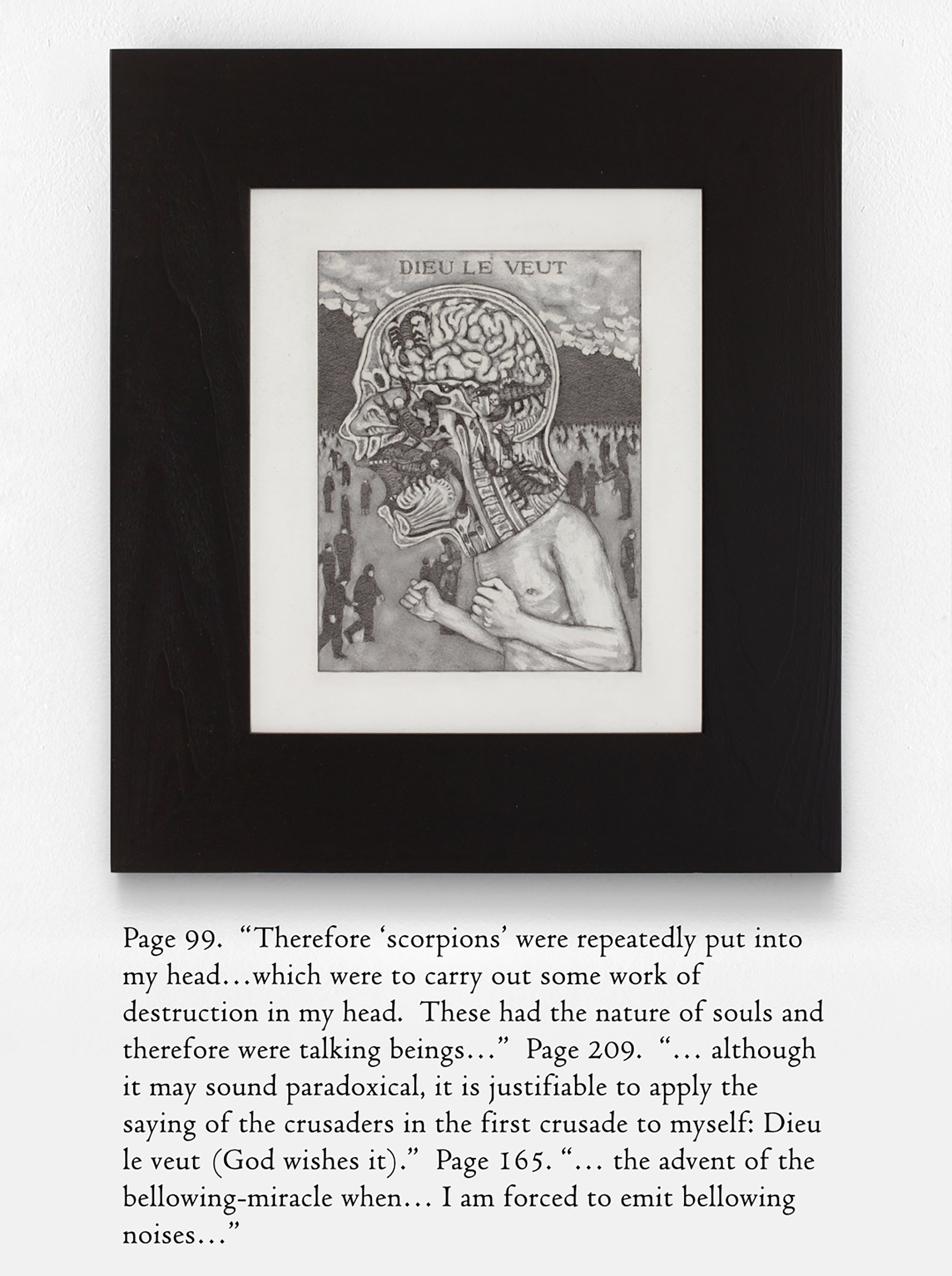

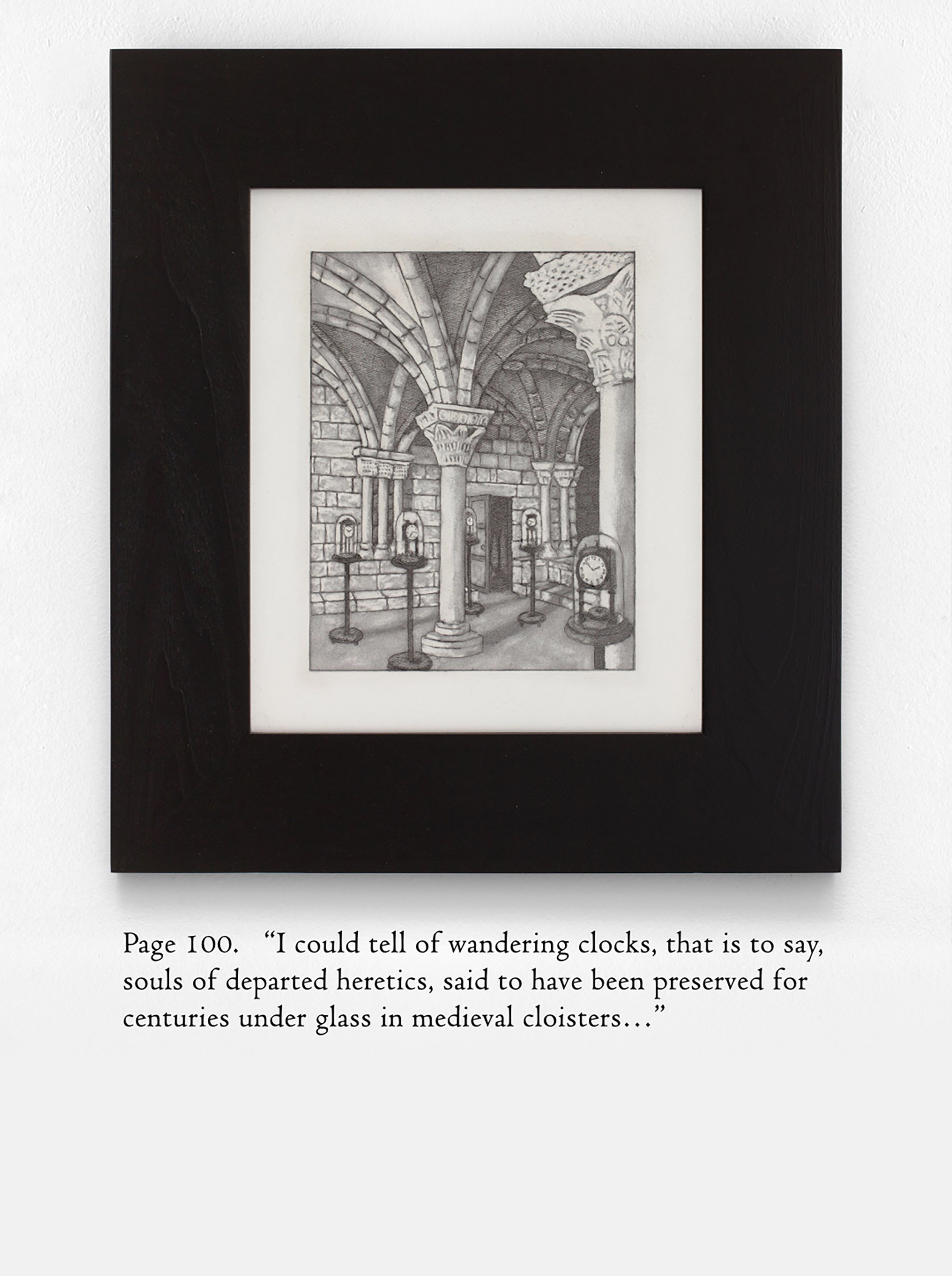

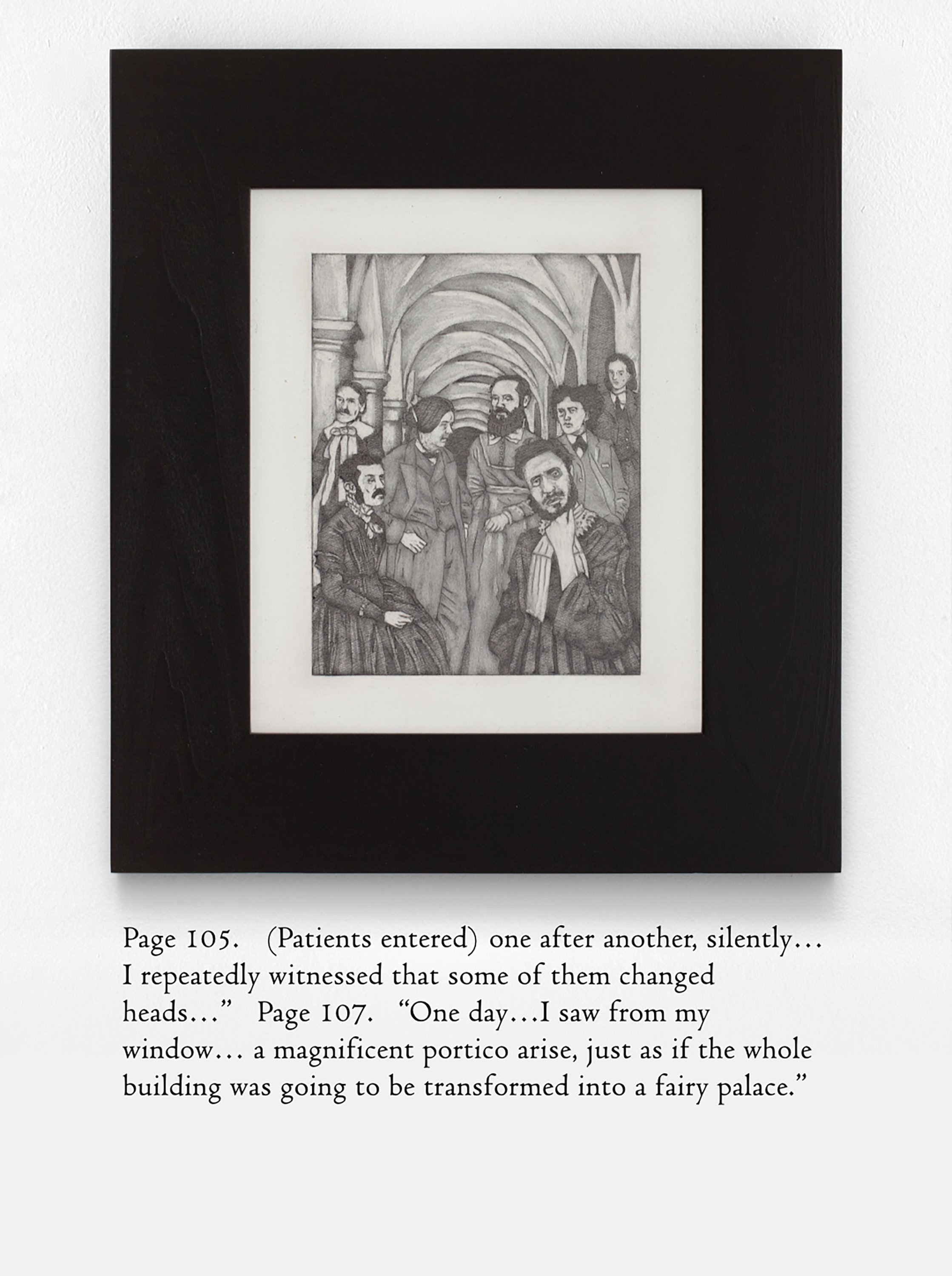

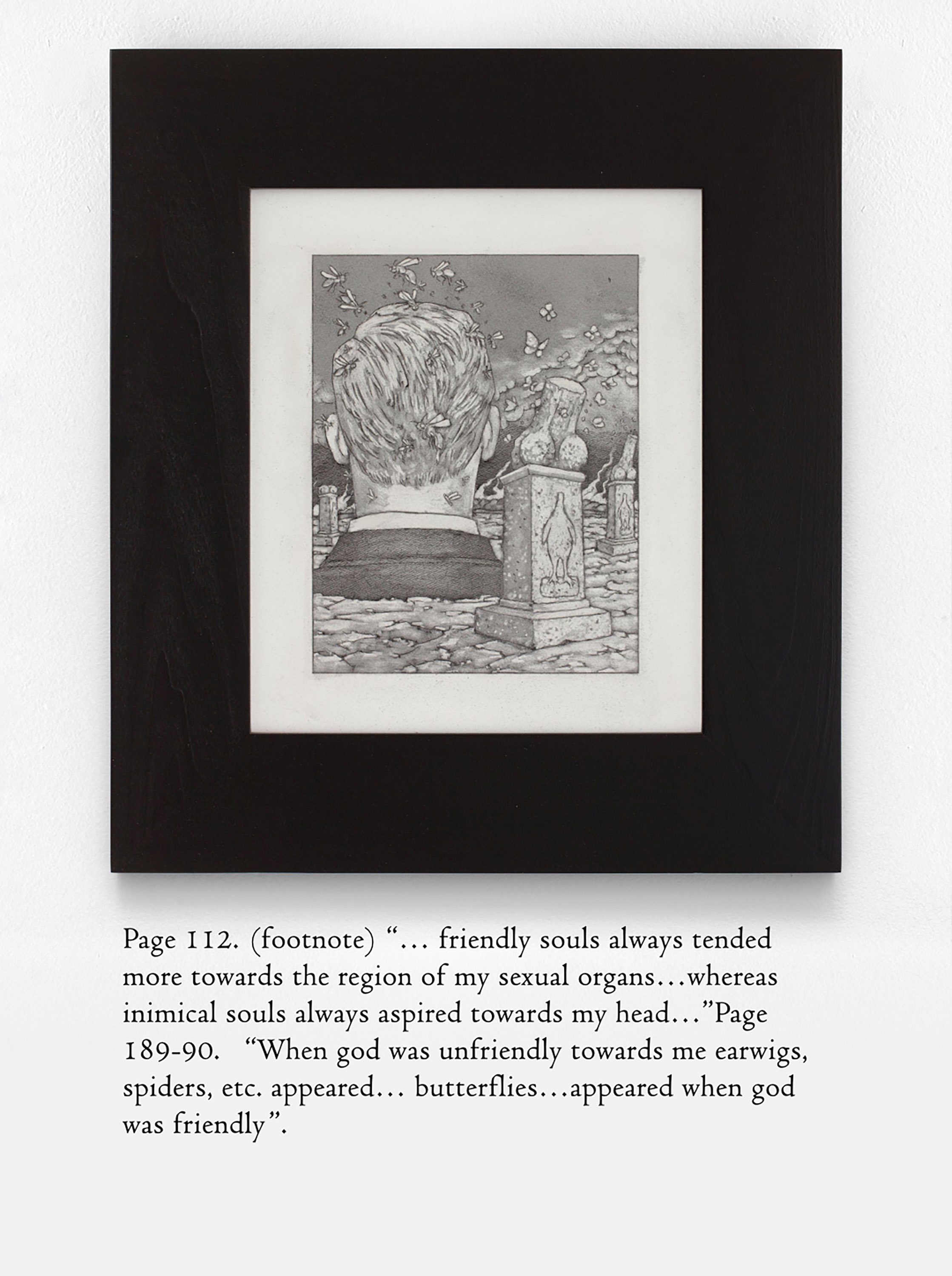

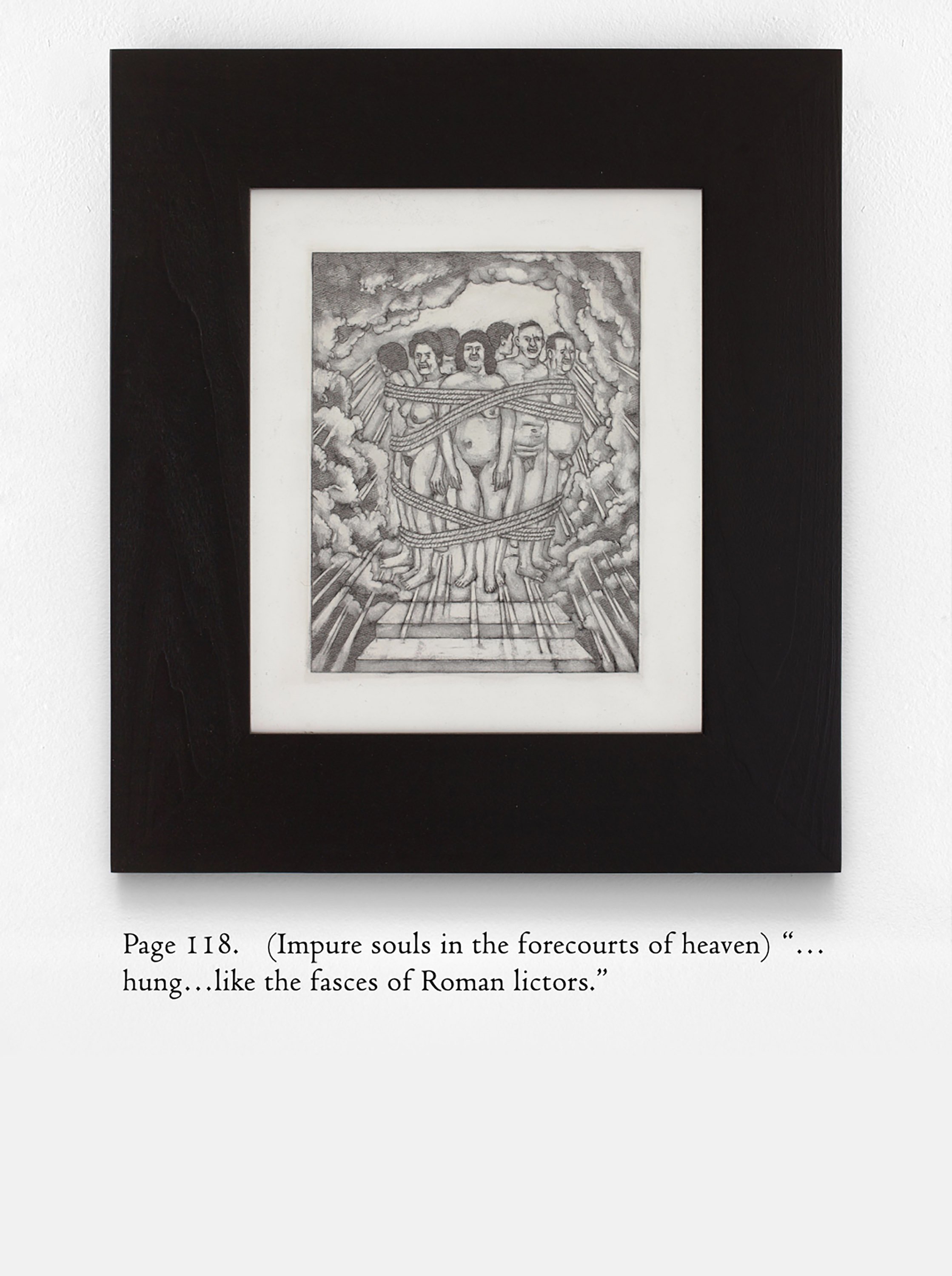

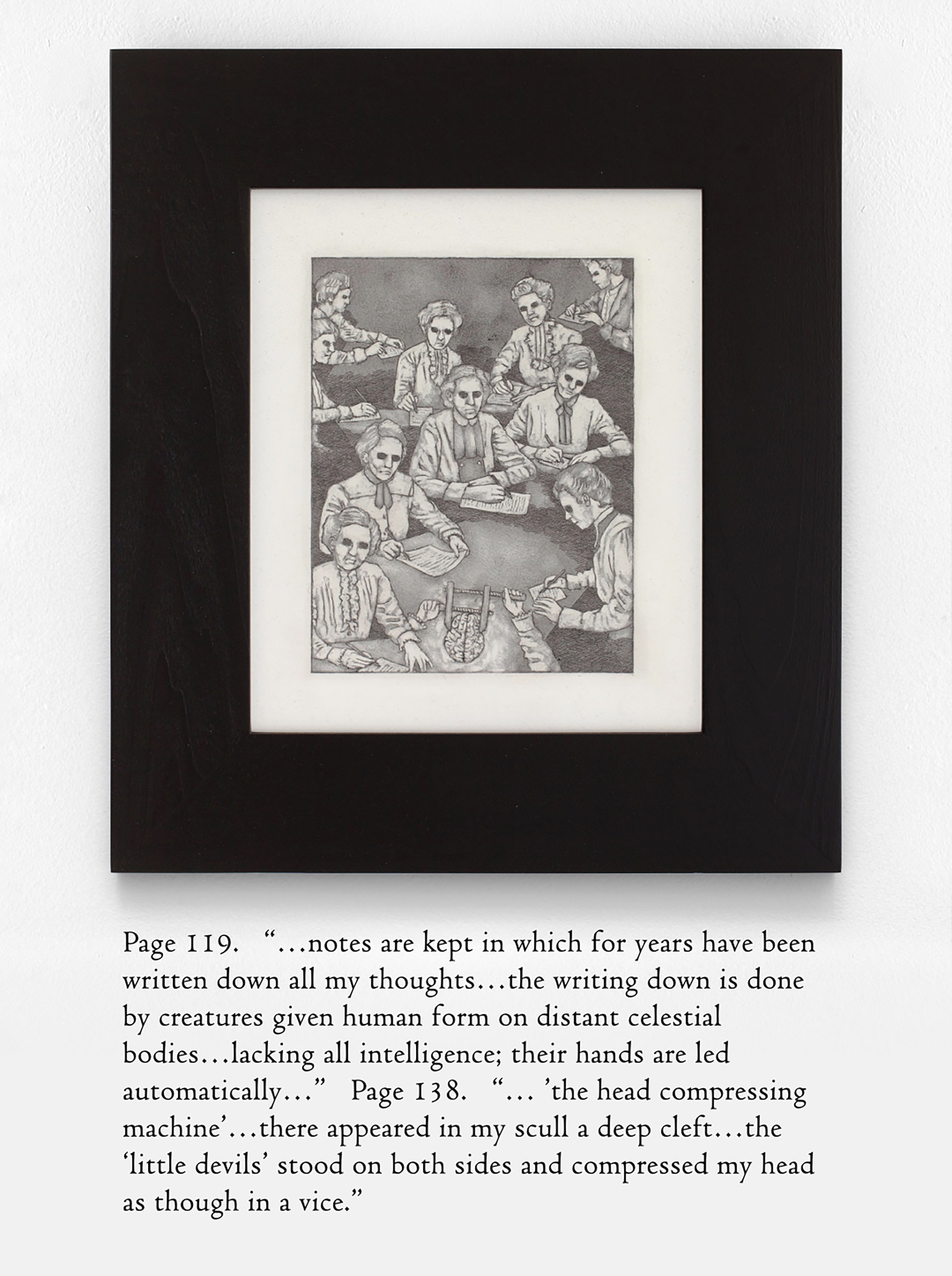

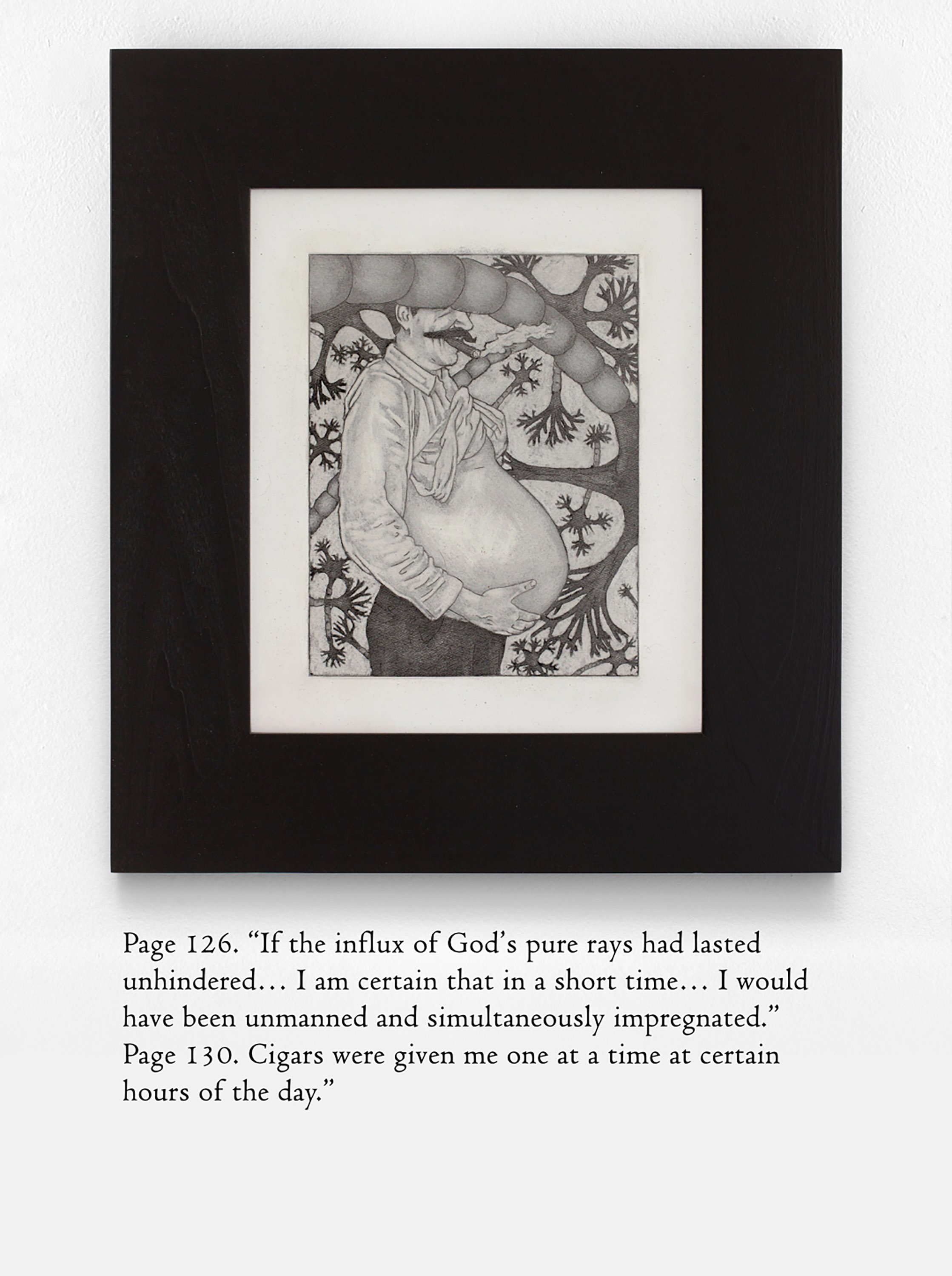

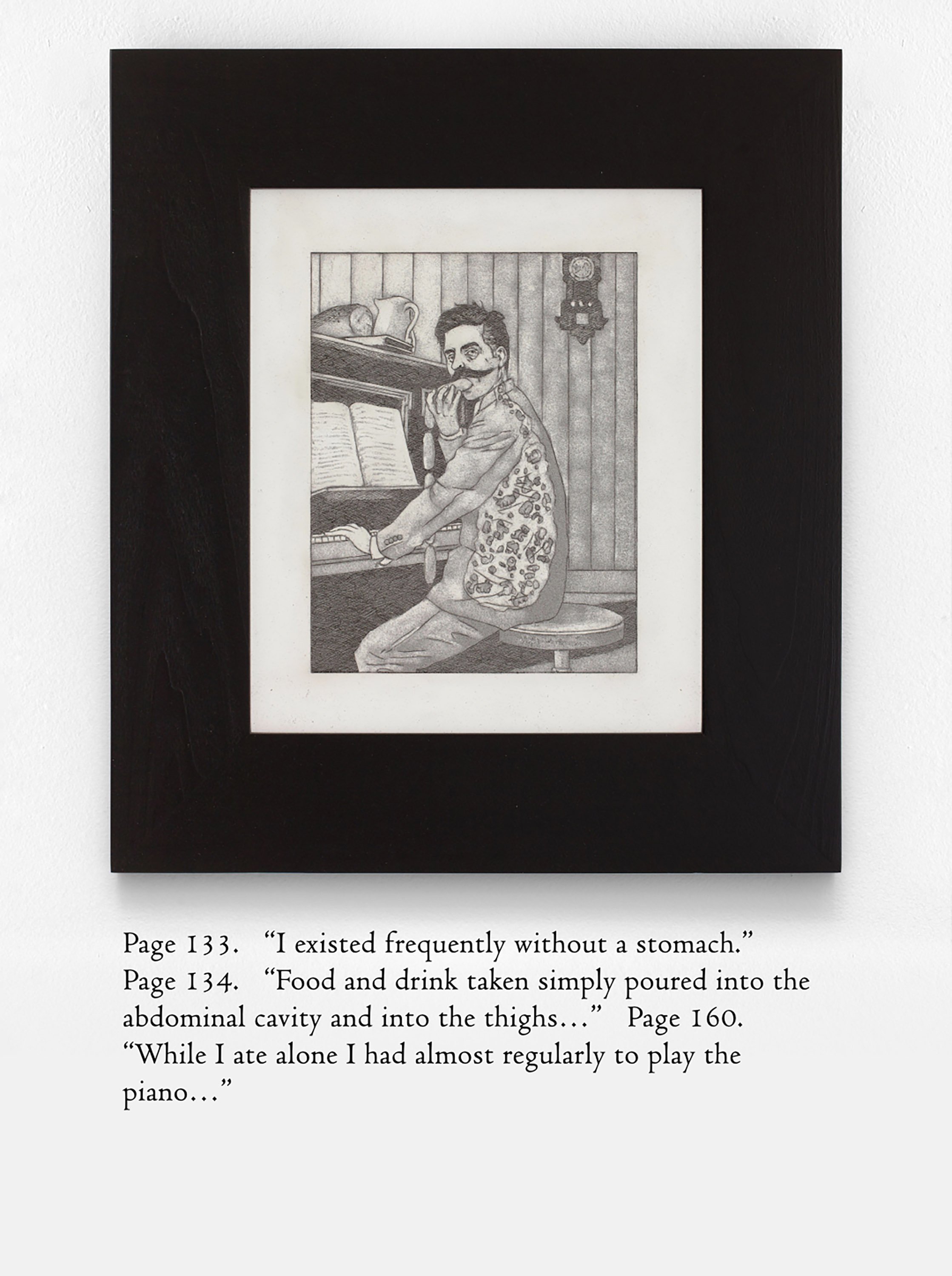

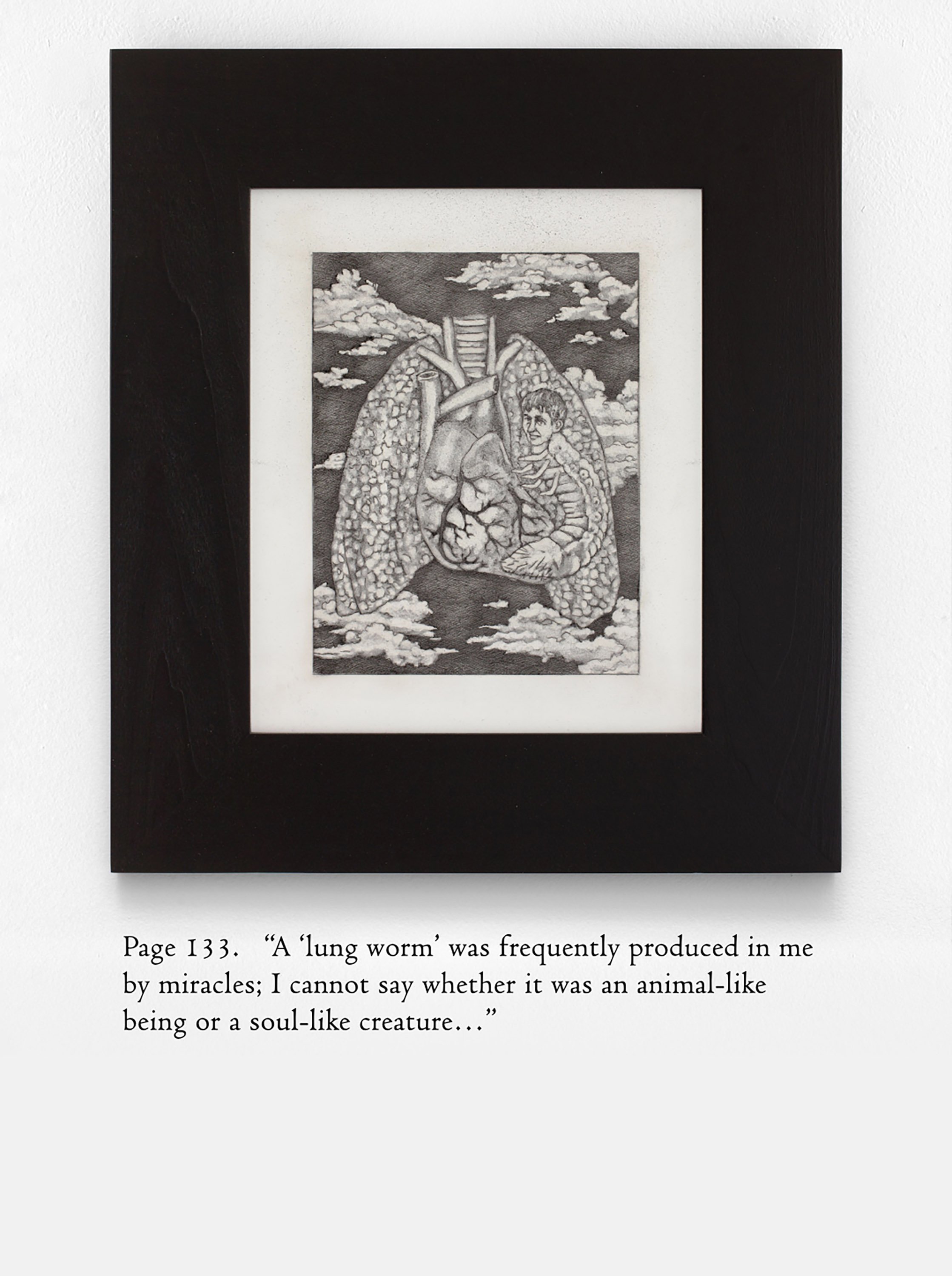

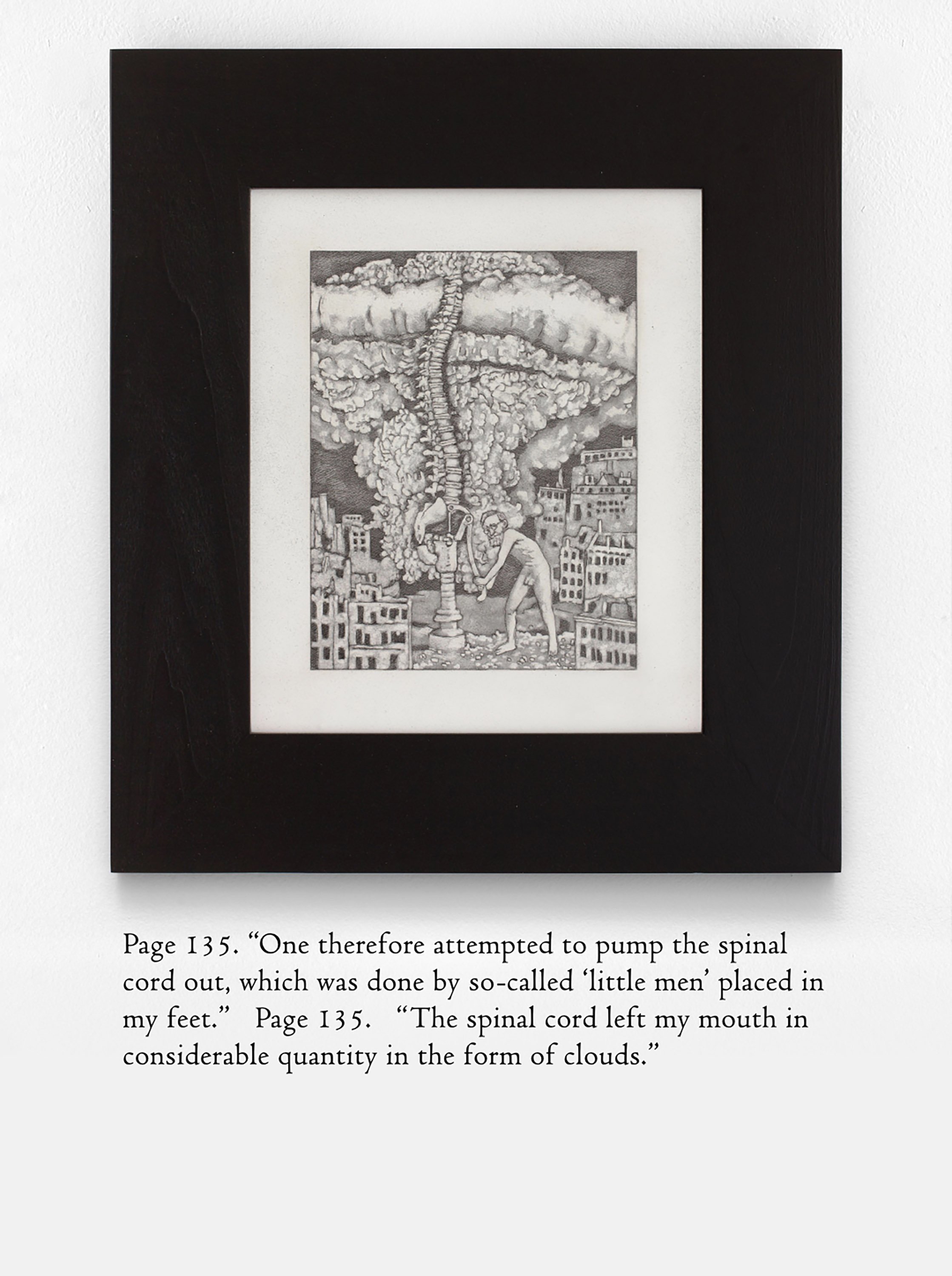

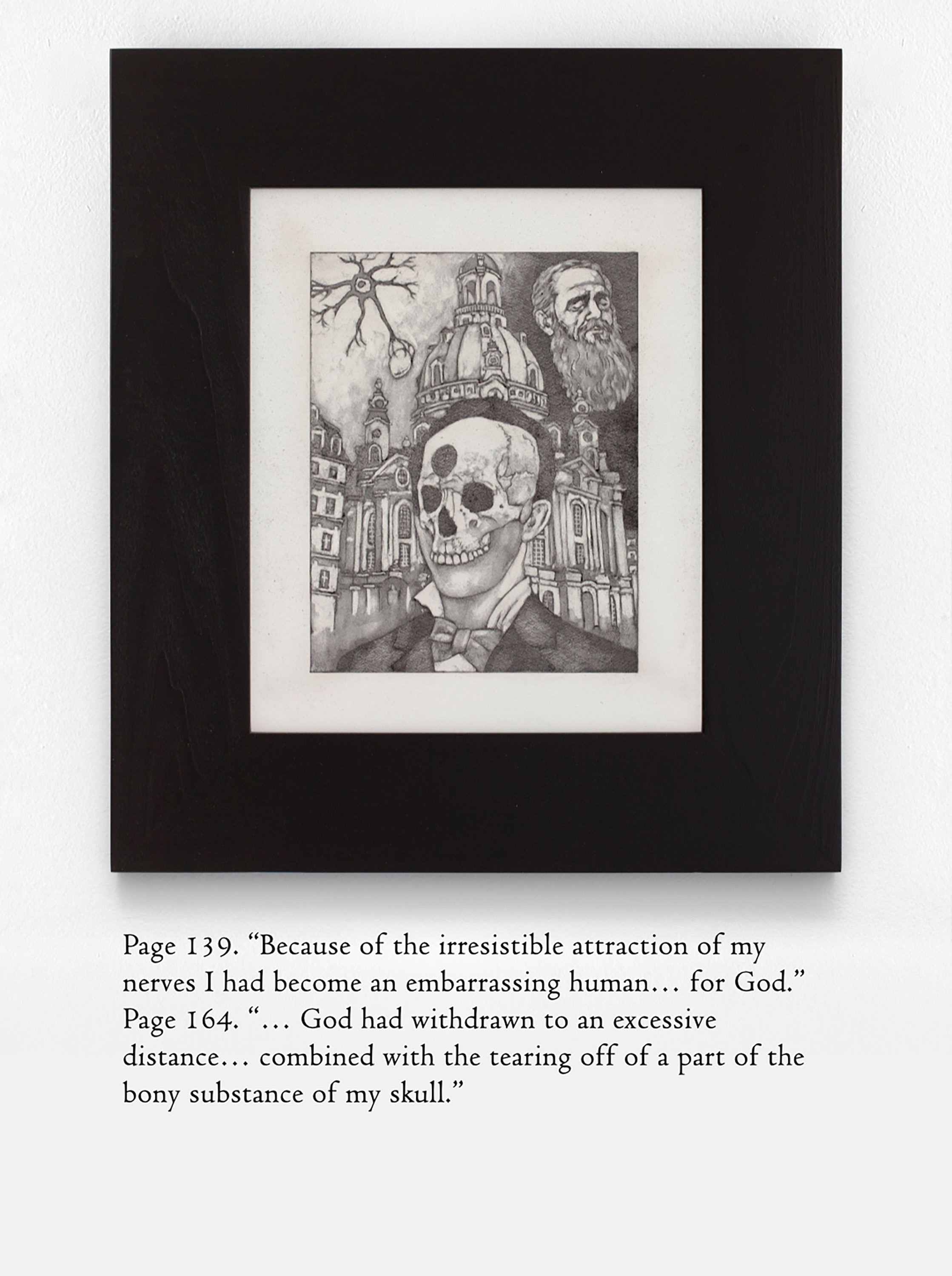

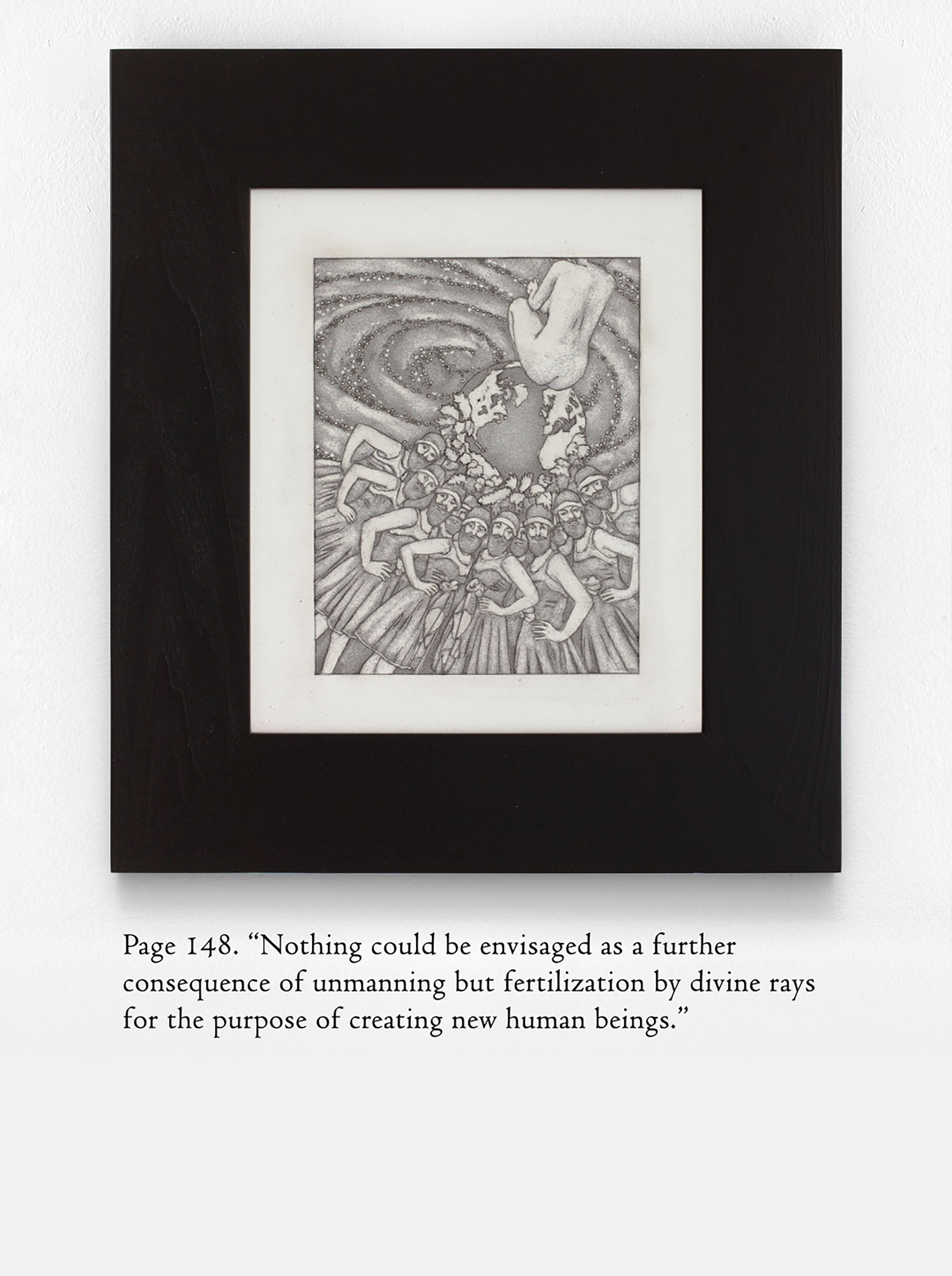

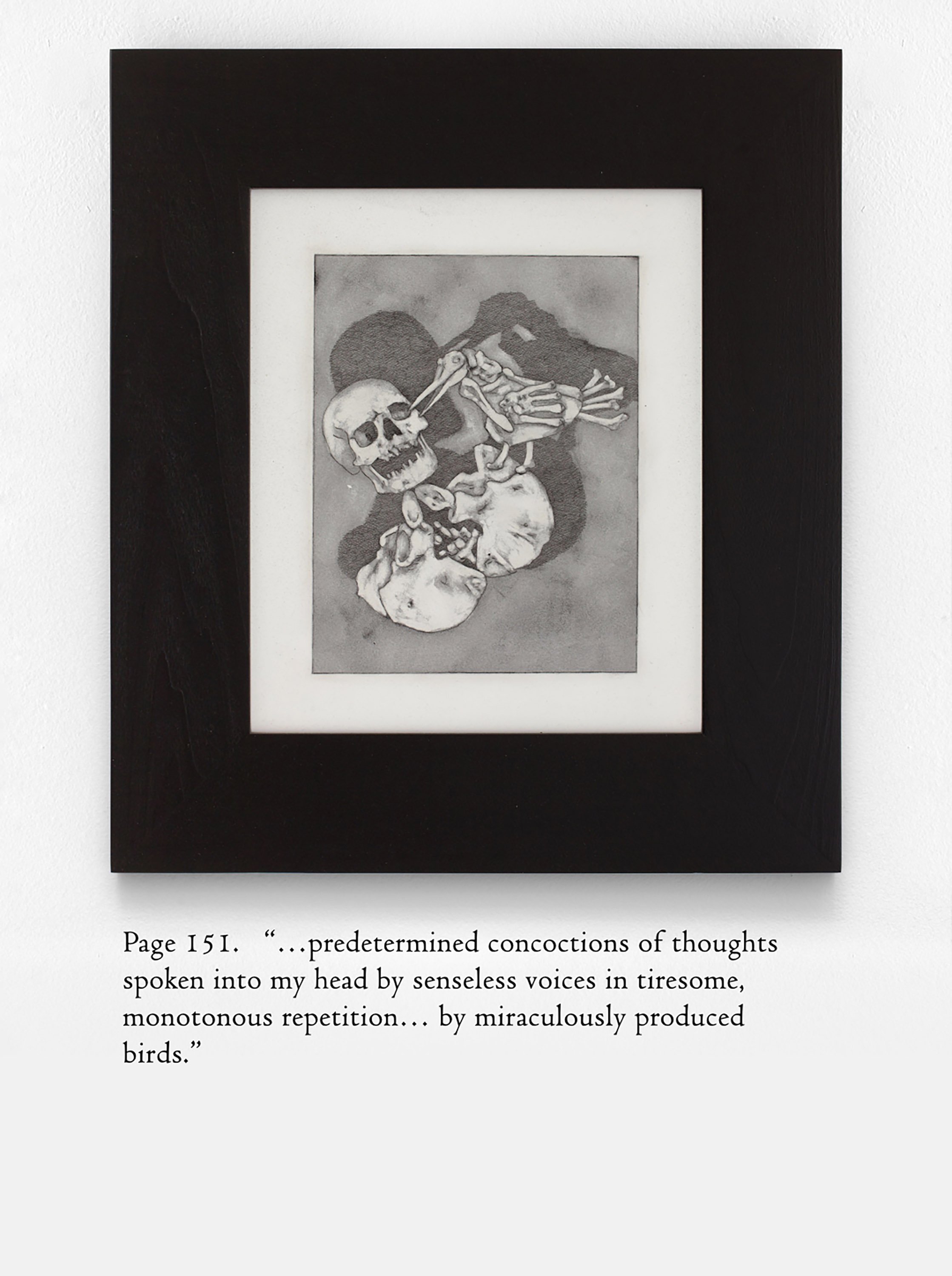

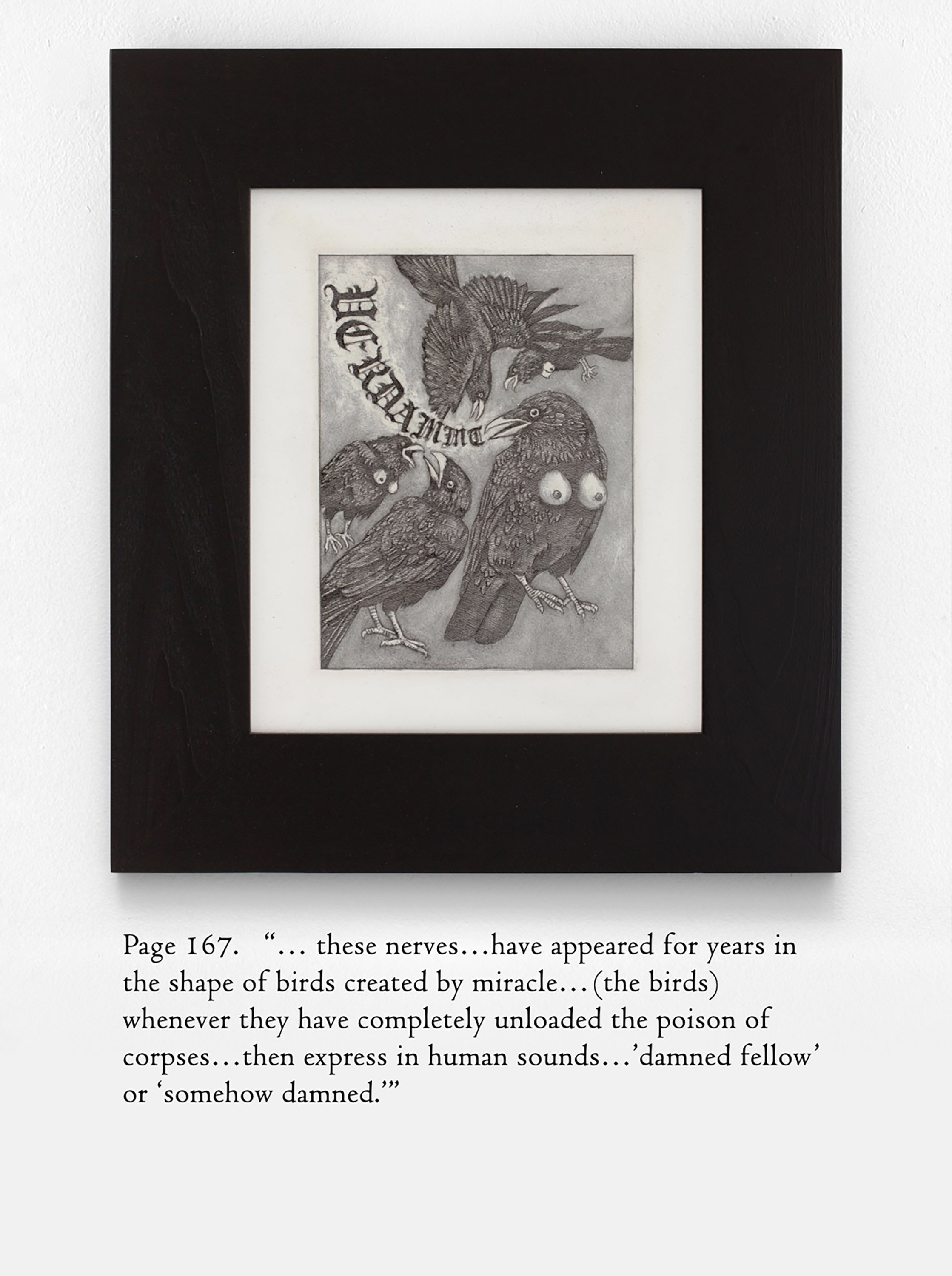

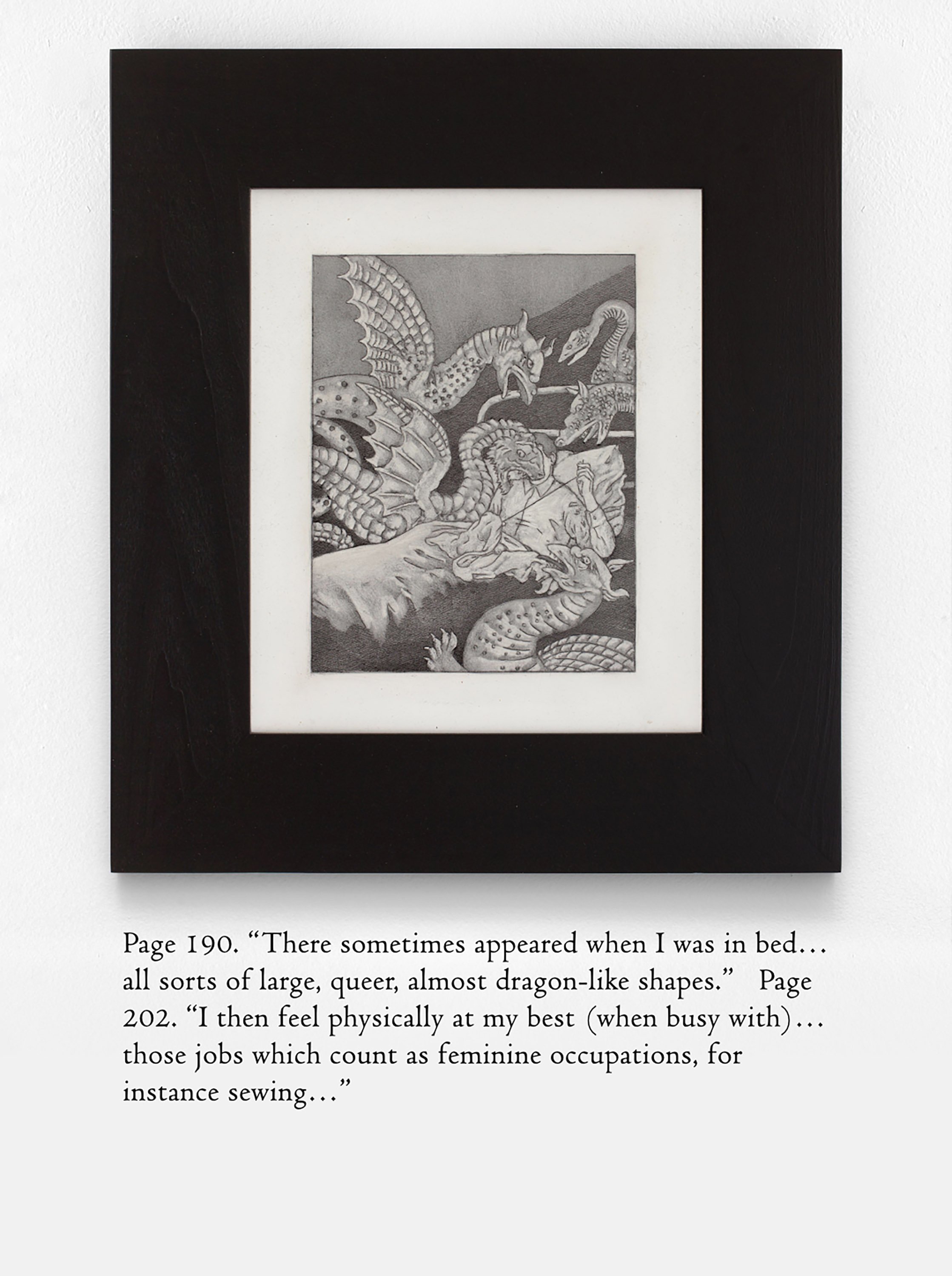

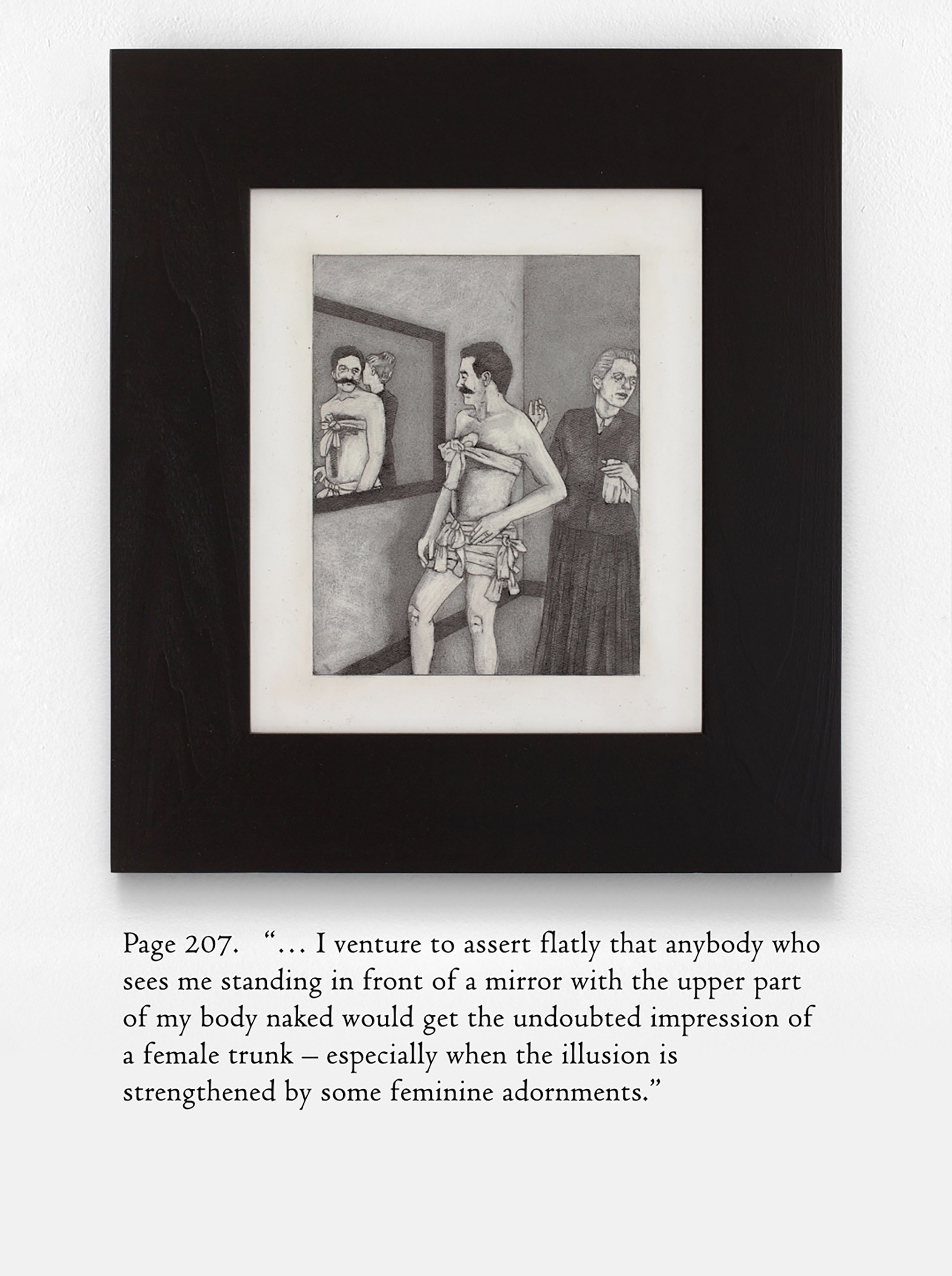

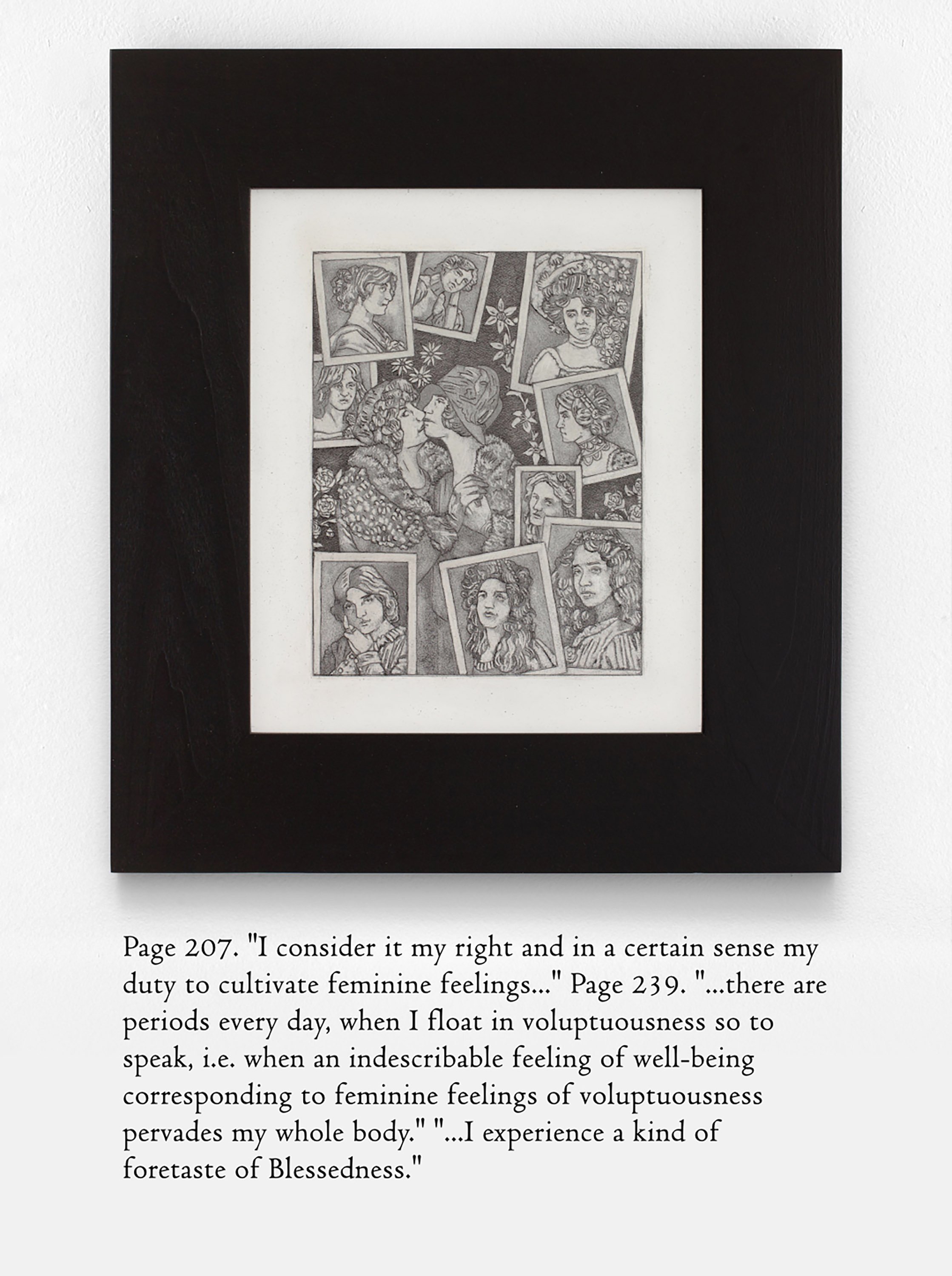

Just as Judge Schreber worked to translate his experiences into words, Undine has done a similar deciphering of Schreber’s writings into complex and ingenious illustrations. Undine’s illustrations are accompanied by Schreber’s texts, enabling the viewer to ruminate first hand through the astute German’s determination to communicate what he knew as reality. Reading each excerpt while exploring the details of the depictions brings to life what inspired the artist to undertake such a beautifully complicated project. Undine’s technique of painting aluminum and then carving black ink into the metal using a stylus creates an effect similar to an etching or even a print. But the metalic sheen and slight indentation in the lines give clues to a hidden process. The lines are incredibly fine and the work is highly detailed with many different styles and approaches being implemented. The cross hatching is especially intricate and create overlapping patterns that are both meticulous and organic. Through Undine’s tireless research of the magistrate turned asylum resident, and his unique process of carving images into painted aluminum, the artist exposes his own mind’s capacity for imagination and empathy. Part scientific analysis, and part whimsical unorthodoxy, the more one explores Undine’s fantastic reality, the more grounded the ideas become. What we’re left with is an understanding that not everyone sees everything in exactly the same way. And haven’t we all felt like that at one time or another?

The Uncanny is a series observational depictions of various microscopic organisms, that could be (and likely are) living on or inside your body. The title comes from Dr. Sigmund Freud’s essay on the subject of the uncanny, which posits that humans experience this phenomenon when confronted with evidence that something they previously realized was not real, may in fact exist.

In this case, we’re confronted with a grid of beings that we’ve learned from experience and thrxough the research of others, are real, but can’t seen without magnification. Humans tend to fear unknown creatures and some of these microorganisms look like the things of nightmares. We like to think of ourselves as clean, and so we politely pretend that these organisms are not crawling all over everything. Some, like the tardigrade, have become cultural curiosities and may look familiar by way of recent stories in the news about their tiny bear-like appearance and ubiquitous survival abilities. Other species, like the hookworm, tapeworm, and common maggot, probably sound familiar, but might not be instantly recognizable. Uncanny is that feeling when you experience something you thought was impossible, and you think your world might have just changed.

The overlap between the Schreberismus works and The Uncanny series has to do with that analysis by Dr. Frued, as well as the idea that both psychological and parasitic afflictions can go unseen, and may be easily denied or ignored. Both can be ugly, difficult to deal with, and cringe inducing, but nonetheless are part of our world. The cognitive dissonance we experience when confronted with something we know exists, but are more adept at living as though it does not, is The Uncanny.

From outside the gallery, visible only to the street, the artist has installed a whimsical shrine to Daniel Paul Schreber, with an ornately framed portrait at the center, surrounded by frippery, a disco ball, and a literal red light. Inside the gallery, the exhibition spreads the works around the walls, intersperced with podiums, seats, reading kiosks and interactive sculptures. The Schreberismus series are hung mostly in an even grid around the 3 inside walls of the gallery. The Uncanny is displayed in a tight grid floating out from the wall with thick ornate drapery hanging behind. On one side of the drapery is a tall depiction of a woman undressing from a full-body latex outfit. On the other side is Kiosk 1: Voluptuous Affliction a sculptural book stand complete with hand-bound volumes on various mental health issues. In the very center of the gallery is a short wide wooden box or step serving as a pedistle for Kiosk 2: The Schreber Cases, another sculptural book stand of sorts, this one including a bell jar containing small porceline birds, a small figure, and human bones. Containted on the shelf are copies of vairous studies and reports on Daniel Shreber. Next to the pedestal is an artist-made stool.

Hanging in the center of the largest wall, between 2 grids of framed images, is Tribute to the Unspeakable a mixed media sculpture incorperating deer antlers, an arrowhead behind a magnifying glass, 3 shot glasses, a back-lit photograph of what appears to be a nudist colony, and the audio of what seems to be a woman half-acting erotic bird-like chirps and shrieks. The references to naturalism, indulgence, faux fantasy, and the preditor/prey relationship, as well as the foreboding title, indicate there is a story to unpack here, but leaves it to the viewer to fill in the specifics.

In the corner is The Case Against Proconsul a large box with a propped-open lid sitting atop a pedistal. Behind glass, on the underside of the lid are several profiles of various mammel skulls carved out of a skull bone. Down inside the box is a a telephone circa 1920 as well as a smaller glass-covered box lit from the inside containing a human jaw bone. Through the phone is audible the voice of the artist reading the text that gives the work its title. A small hand-made book with a written version of what’s being spoken through the phone sits next to the sculpture. The story is of how mammals first migrated from the swamps of what is now Euorpe into the continent of Africa, before giving rise to what became primates. The story is factual in nature, compelling and thoughtfully told

Dreaming Schreber

Paul North

In the warm middle of society, where everyone is comfortable, there are things that don’t show themselves, shadows, forces, connections. Denial is too weak a word for the attitude that keeps them hidden. Psychosis is another word, a clinical word, for what lets them show. It is not a chemical problem but a response, in some cases the right response, to the ravages of a social order that a contemporary of Schreber argued kept individuals separated from one another in cage-like existences. Social theorist Max Weber considered the mark of modernity to be the isolation of people from one another. Were the links between them gone? No, just gone underground.

Take the most upstanding person in all of Germany, not just any gentleman—Daniel Paul Schreber. He occupied multiple positions. Bourgeois subject, man, citizen, and in all this at the same time he was the designated bearer of social rules. I shall be a man, a bourgeois individual, and a citizen of this state and upholder of its laws and conventions. And I shall also be a judge empowered to condemn others who break those laws. In the midst of society, as an upstanding member and as its empowered enforcer, Schreber saw and felt things, within apparent normalcy, that were highly abnormal, things that went beyond human understanding, as he put it. Visions were given to him, but as he himself admitted, understanding was not.

You could say Schreber “saw,” without understanding, the forces that hide, and then he took rebellious positions toward them—which landed him in institutions for the insane. He called what he saw by a general term, “nerves,” and they fascinated him. Nerves seem to have represented for him a tissue of existence, a total mesh of links by which all things that seemed separated were in fact intimate with one another, links chiefly among nature and human beings and God. Schreber calls himself, somewhat ironically, a “Nervenkrank,” a German term of the time for what psychiatry calls now “mentally ill,” though the newer term does not add much understanding. Schreber understood that the medical term “nerve sickness” was in fact a correct designation, but for the wrong reasons. From his perspective, he was the only one with vast enough and open enough sensitivity to the universe to sense the true connections among things. God understood the speech of all nations because he was connected to their nerves—and Schreber experienced a related though inferior “inspiration by way of nerve-contact.”

A clinical gaze misses the fantasies here, the desires. Schreber desired, as the symptoms make clear, to bring the linkages among things to appearance. This was something like a desire to feel the world as a set of complex interdependencies. He also desired something less grandiose, a child’s wish. He desired to be felt, in turn, by the world, to register directly in God’s nervous system. Contact was a gift, a miracle, but it had a cost. He got what he wished for, at the expense of normalcy, not to mention his energy. After six years of direct inflow from God’s nerves into Schreber’s body, his nerves began to lose strength; he felt violated and exhausted.

Schreber’s nerves entered into the public nervous system. He must have intuited how important his fantasies would be to others. Fascination with Schreber is well documented—his memoir is a hot seller; it has been translated into many languages; and many famous intellectuals have written on it. Friese Undine calls this effect “Schreberismus,” a syndrome in itself, which Undine takes as his job not to cure but to explore. It is an artist’s right to proceed by fascination. And fascination with others’ fascination is like psychoanalysis of culture. An artist can freely and without fear take a share in psychosis, to find what is salutary there. Schreber’s nerve-visions have fascinated people almost always in a clinical or conceptual way, as though the judge’s wishes and intuitions had to be safely reduced to a sentence or two of knowledge. What if, instead, we could enjoy his megalomaniacal, bizarre, and strangely satisfying visions—what if instead of diagnosing the man over and over again, we saw what he saw? That is undoubtedly too simple a wish, though it is probably the driving wish of Schreberismus. Undine’s art is rational insanity, conscious self-directed seeing of the wild visions. Undine puts them in order, sutures them back into our conversation publicly. They appear stranger even than the descriptions in Schreber’s memoir, stranger and, surprisingly, less threatening, kitschy even, like objects in dreams. We dream to be able to dream like Schreber did, of the vast, the high, the totality of hidden linkages. Recognizing this impulse, Undine leaps in gives us our wish—so that we can examine it.

Statement from the artist:

“Daniel Paul Schreber was a German judge who after suffering a nervous breakdown in 1884 was institutionalized, finally being placed in Sonnenstein castle near Dresden. In his book titled “Memoirs of my Nervous Illness” he tells the reader that he had become the last living human on earth and all of the human forms around him were reanimated corpses, or “fleeting improvised men”. It was his mission to repopulate the earth. He would do this concentrating his mental energy on his body, making his breasts expand and hips broaden thereby seducing God who would inseminate him. Schreber would then give birth to a new race of beings. Also, befitting the Biblical scope of his mission and his role as a prophet he must become Jewish. This and many other miracles took place around him, in every part of his body and in distant reaches of the universe. These drawings are based on some of the miracles Schreber describes. The medium is ink and spray paint on aluminum. The quotes accompanying the drawings are from the 1988 edition of the Memoirs from Harvard University Press.”

- Friese Undine

Undine has exhibited his work in galleries, museums, and cultural centers around the world for over 3 decades. He has a prolific portfolio of work including a series of over 2500 portraits of world leaders and villains, and has been commissioned to produce multiple large-scale murals. Undine works in multiple mediums and disciplines including oil on canvas, ink and paint on aluminum, and mixed-media sculptures. He was selected for the 2003 Margaret Klimek Phillips Foundation Fellowship. View more of Friese Undine’s work here.